Nearly two years of litigation between Kansas City officials and local urban farmers has seemingly come to an end. In late January, the City Council denied Urbavore Urban Farms’ Master Plan Development proposal. But what exactly is a master plan development? Who is Urbavore Urban Farm? And why did it take two years for this saga to conclude?

The first two questions could be answered in simple terms. A master plan development — or MPD — is a large-scale, long-term proposal that outlines a plan to physically develop (or redevelop) a community. Urbavore Farm, one of Kansas City’s largest and longest-standing urban farms, sought approval for an MPD to expand its operations.

An MPD is typically pursued for “urban renewal” projects — often framed as efforts to “revitalize” certain areas (mostly Black and working-class) through housing development and other community infrastructure (e.g., the Power & Light District). But MPDs are rarely used for agricultural development.

So why was Urbavore Farm pursuing an MPD in the first place?

Because securing an MPD would have solidified Urbavore’s long-term control over land in Brown Estates, a heavily-Black populated neighborhood in Kansas City’s 3rd District. This is where colonialism and the legacy of regenerative agriculture come into play.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines colonialism as “a practice of domination, which involves the subjugation of one people to another.” One of the ways colonialism manifests today is through land use policies that allow wealthier, white-owned ventures to entrench themselves in historically Black communities — often under the guise of sustainability and development.

Regenerative agriculture is an afro-indigenous farming approach that uses sustainable food-growing methods to restore natural resources rather than deplete them. While white-led ventures like Urbavore profit from on regenerative farming practices, Black farmers were historically denied land ownership and the ability to sustain their agricultural traditions.

Just last month, the USDA rescinded funding for the Ivanhoe Farmers Market, a Black-run initiative that provided fresh food access in Kansas City’s historically Black Ivanhoe neighborhood.

Meanwhile, Urbavore and other white-led ventures continue to capitalize on regenerative farming while bypassing community input and attempting to secure land through city-backed processes.

To put it plainly, white farmers moved into a Black neighborhood to pursue their endeavor, adopted afro-indigenous agricultural practices, and then sought legal protection to solidify their presence — despite its negative impacts on neighbors.

This effort — framed as a sustainable initiative — led to countless hours of litigation. Urbavore spent nearly two years presenting an MPD plan to the Board of Zoning and Adjustment, City Planning Commissions, and Neighborhood Planning before hitting a roadblock with the City Council. Over that two-year span it became evident that Urbavore’s pursuit of their master plan was nothing more than a micro-colonial venture campaign built on performative activism.

Urbavore Farm and Compost Collective KC

Urbavore Urban Farm is the second farming venture of Brooke Salvaggio and Daniel “Dan” Heryer. It occupies roughly 13.5 acres of land at 5500 Bennington Ave. and sits behind a row of residential homes that stretch along 55th Terrace.

Salvaggio and Heryer purchased the land in 2011. At that time and to the understanding (and approval) of Urbavore’s neighbors, it would operate as a small vegetable-producing family farm, Brown Estates homeowner Carrena Moultrie told The Defender. And for the most part, it did.

That was until 2021, when Salvaggio and Heryer purchased Compost Collective KC (CCKC). The purpose of this second business was to expand their existing composting efforts. Composting is a regenerative farming practice that involves recycling organic wastes, such as food scraps and yard trimmings, to enrich the soil. For Urbavore Farm, CCKC and its nearly 3,000 subscribers, composting helps produce rich, nutrient soil from what would otherwise be landfill waste.

Generally speaking, composting is a practice that should not only be supported, but set as the standard. It provides many benefits both economically and environmentally. It is an ideal component for farmers who utilize regenerative farming practices, but it is not void of any drawbacks.

CCKC uses a community-based composting model, which is organized within a local community to manage organic waste rather than large industrial composting facilities. Their organic waste is collected throughout Kansas City and brought through the Brown Estates neighborhood by way of 55th Terrace. This type of community-based composting — in particular — has the potential to attract pests, wild animals, and permeate odor. The composting model may also face challenges related to regulatory compliance, according to Boise State University.

It is regulatory compliance, otherwise known as zoning codes, that Salvaggio and Heryer were challenged with. But it wasn’t the first time.

In 2007, Salvaggio created Badseed —a storefront farmers market located at 1909 McGee St. The market sold produce that was grown on Salvaggio’s 2.5-acre farm located near Bannister and State Line Road. That market was hit with zoning violations for operating a “business” in a residential zone. Lack of nuance and varying interpretations of the code may have allowed Badseed to stay open as they claimed to only sell produce. But it was ultimately closed in 2016.

Fast forward to 2023 and Salvaggio was determined to not let a similar fate fall upon Urbavore Farm and Compost Collective KC. She and her partner Heryer spent the next two years disputing more violations. They challenged their At-Large District Rep Melissa Patterson-Hazley and Mayor Quinton Lucas to visit the farm, created a website for the supporters to write letters, and rallied support from their online followers. But the pursuit of a Master Plan Development complicated efforts to reach a resolution.

Taking Up Space

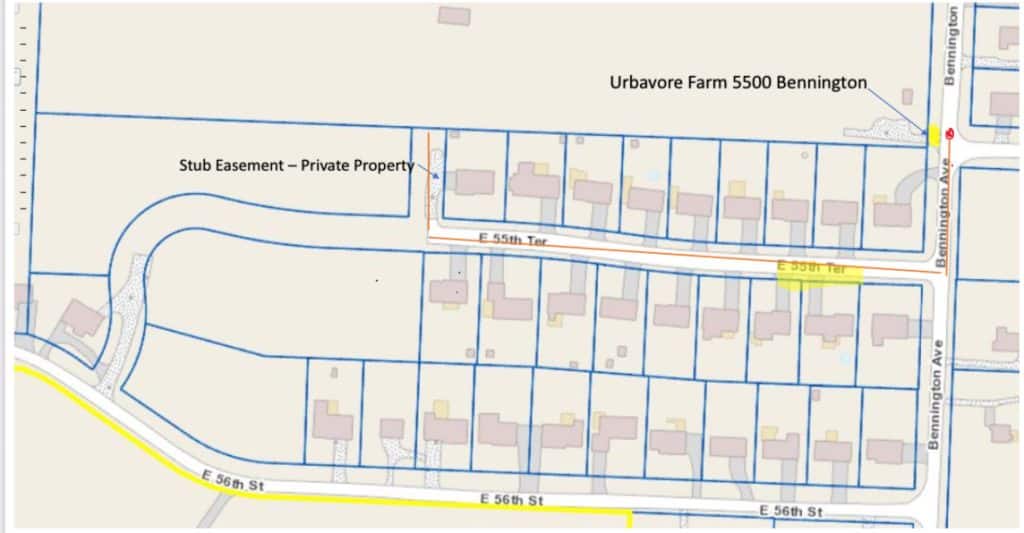

Longtime Brown Estates resident and mother to Carrena Moultrie, Leah Suttington, has owned land in the Brown Estates for over 30 years. She owns the two homes on each side of the dead-end of 55th Terrace. And it is 55th Terrace and the underdeveloped street – not the farm’s address at 5500 Bennington Ave. – that Urbavore uses as the main entrance to their composting site.

Before Urbavore moved to Brown Estates, the city owned the 13.5 acre property , which was originally a baseball field. According to Moultrie, the city was supposed to extend the residential area by building a street off of 55th Terrace. However, the area was never developed and remained vacant for decades.

The underdeveloped street off of 55th Terrace was never extended, and the city retained the right to allow access to it through easement — a legal agreement permitting the use of someone else’s land without owning it. Through this easement, the area would later become the entrance to Urbavore Farm’s composting facilities.

According to Suttington, that entrance was used as a private access point to her driveway for several years. But when Urbavore expanded their business, Dan Heryer — on his own accord — illegally extended the entry path with gravel. This change allowed trucks of varying sizes to drive up the dead-end road and use the gravel road to deliver the food waste collected from CCKC’s monthly subscribers.

This “entrance” was also an access point for Urbavore customers who participated in their community-supported agriculture program to pick up their orders on Thursdays, an employee entrance, and the front door for any special event the farm hosted. These elements, along with the compost drop-offs, resulted in increased traffic.

While Salvaggio and Heryer claim traffic increase was minimal, neighbors report that anywhere between 100 to 300 cars drove up 55th Terrace in a single day, often riding over curbs and damaging private property when congestion was high.

Suttington said Urbavore’s commercial sales day brings the heaviest traffic, but there is constant traffic from visitors, employees, and waste trucks. With these new conditions, the peace and quiet that dead-end once afforded Suttington and others was destroyed.

The unresolved tensions regarding the entry path and other disputes regarding the farm escalated and brought forth city officiating. In 2023, City Inspector James Duddy cited the farm and its composting operations for four zoning violations including compost facility, retail sales, vehicle use areas, and shipping containers.

One of those violations cited Code 88-238, which regulates composting facilities. City officials determined that Compost Collective KC was a “primary use” rather than an accessory to the farm and therefore operating at the scale of a facility. Composting facilities are subject to specific zoning standards outlined under code 88-328-02. Salvaggio and Heryer, however, felt this ruling was a mistake since they received approval to operate the compost as an accessory from the city manager’s office just two years prior.

But by 2023, The Board of Zoning Adjustments determined the exact opposite. It is this type of contradiction that highlights how such nuanced language used for zoning and coding regulations — which are historically racist at its core — can be misunderstood, misinterpreted, misapplied and/or manipulated for self-interest.

Pursuing the Master Plan Development

Urbavore and CCKC were faced with two choices: appeal the violation or request rezoning. Salvaggio and Heryer disputed the violations during a 2024 January zoning hearing. Rather than ruling on the matter and levying a penalty, the Board of Zoning Adjustments voted on a six-month continuance to allow Urbavore to pursue an MPD. Urbavore claimed that their MPD would correct the violations and address their neighbors’ concerns.

That March, Urbavore launched a GoFundMe campaign titled “SAVE URBAVORE & Compost Collective KC!”

Shortly after, Salvaggio and Heryer contracted national architect firm BNIM to design a 30-year master plan for rezoning. In that plan, Urbavore vowed to “build a new access drive” using their address at 5500 Ave. ( as illustrated on the design mockups). Their MPD also included compost heated greenhouse, community solar pavilions, nature-based learning, and mixed-use community space.

From there, Salvaggio and Heryer began the months-long rezoning process to approve their master plan. That process spanned from July to January, with multiple committees and City Council hearings.

In September, the City Planning Commission recommended approval of the plan by a 5-1 vote. But when Salvaggio presented the plan to the Kansas City Neighborhood Planning and Development Committee in October, the committee recommended that Kansas City Council reject it.

Following suit, as reported by The Beacon, City Council voted no and referred Urbavore to make adjustments that would move the proposed new entryway for the compost piles further north — and away from residential homes. This decision sent Salvaggio and Heryer back to square one.

Salvaggio claimed that Urbavore could not make the requested changes to the MPD. She was adamant that moving the entrance further north, closer to the middle of Bennington, would destroy the farm. She also named money — despite a GoFundMe campaign with nearly $80,000 — as another hurdle. Nonetheless, Salvaggio and Heryer went through a second round of hearings with the same MPD. And it was this past January that the City Council voted no a second time.

The lack of coordination between city departments, the complexity of zoning language, and the lengthy legal processes were not easy for either Urbavore Farm or Brown Estates residents to navigate. The process caused confusion and delays. And for Urbavore and the neighbors, the process costs time and money. However, the road that Salvaggio and Heryer chose to continue on was not just an attempt to rezone a predominantly Black neighborhood, it was also a demonstration of performative activism.

White Victimhood and Virtue Signaling

“Save the Farm” is the slogan for Urbavore’s campaign. The owners have used it to garner support as they push forward with their proposal.

Upon hearing the slogan, one may assume that the farm’s existence is in jeopardy. But from what? Salvaggio and Heryer own the land Urbavore occupies, so there is no threat to the farm’s existence. In fact, there is no threat to the farm as a whole. The only request from the City Council was that they find a new entryway for their compost operation. So why not use a slogan that addresses the actual issues instead of creating a misleading narrative?

It’s because “Save the Farm” is the perfect rallying cry for a campaign rooted in self-serving advocacy. It allows Brooke Salvaggio — as the outspoken mouthpiece for Urbavore and CCKC — to create inflammatory rhetoric about her Black neighbors. It has allowed her 16,000 online supporters (both Instagram and Facebook) to believe something that is not true. It enables Salvaggio to manufacture white victimhood and cloak virtue signaling in language that advances a micro-colonial agenda.

The Dangers of White Victimhood

In her book titled Citizen: An American Lyric, poet and essayist Claudia Rankine writes,

“Because white men can’t police their imagination, Black men are dying.”

This quote explores how white victimhood impacts the Black community in such a harmful way. When white people see themselves as victims, the outcome of it can be deadly — but it is just one outcome of many possible outcomes.

The Rosewood Massacre, for example, is the story of white woman who falsely accused a Black man of assault. This ignited a white mob from a nearby town to terrorize and destroy the Black town of Rosewood, Florida. Several Black men, women, and children were killed and those who survived fled to nearby towns and never returned.

White Narrative Building

Over the last two years, Brooke Salvaggio has used Urbavore’s public Instagram and Facebook page to weaponize her white victimhood. Those exposed to it — and who choose to believe it — view her as a sympathetic figure dodging hurdles to overcome an unjust system that imposes its will against her at every turn. In reality, Salvaggio’s use of victimization is a strategic method that demonizes the Black residents of Brown Estates, portraying them as aggressors rather than stakeholders.

In an article published in The Atlantic, history professor and author Lawrence Glickman attributes white victimhood to a conservative concept that believes “white people in the United States are under siege.” Glickman later goes on to describe the three tropes of white victimhood: inversion, projection, and victimization. Salvaggio is a common player of the last card.

Salvaggio uses victimization as a tactic to distort perceptions, portraying herself as a target of injustice. As social justice theologian Autumn Brown explains, “Victimization is a highly sophisticated and elegant defense mechanism, a product of a highly sophisticated and elegant psychology, that supports participation in white supremacy, a system that is most highly effective at replicating itself.”

Salvaggio’s victimhood is layered with a level of callousness toward her Black neighbors; it not only demonizes their character but dehumanizes them as people. On January 9, she posted a “victory” image to Instagram following a zoning adjustment hearing with a caption referring to the unnamed neighbors and city officials as “monsters” and insinuates that something is “festering” in the background.

Her white victimhood is no less dangerous than that of Carolyn Bryant Donham, the woman who accused 14-year-old Emmett Till of whistling at her. Donham’s false accusation resulted in Till’s murder and lynching at the hands of two white men.

In another social media post, Salvaggio accuses her neighbor of intentionally endangering her customers when they placed a trailer in their driveway and partly on the easement street off of 55th terrace. Salvaggio exaggerated the neighbors actions with words like “crammed” and implied that the neighbor created a sense of danger.

Salvaggio’s narrative is laced with rhetoric that maligns her Black neighbors and creates this false sense of a “threat” that needs to be exterminated. As casual as her Instagram posts and captions may seem, her victimhood messaging is harmful and, at its most dangerous, it can lead to deadly and irreversible outcomes.

Black Tokenism

Tokenism refers to the practice of including a few individuals from a marginalized group — Black people in this context — to create the appearance of diversity. It exploits the concept of diversity by objectifying individuals and using their presence as a form of virtue signaling, like a puppet master pulling the strings. It merely creates a false sense of progress and equality.

All you have gotten is tokenism — one or two Negroes in a job or at a lunch counter so the rest of you will be quiet

Malcolm X

While Salvaggio claims the support of Urbavore is diverse, the support group that sits behind her hearing-after-hearing tells a different story. It’s a mostly white middle-aged group of people who have been deceived and believe the image that Salvaggio portrays. Their unwavering support and unwillingness to question this facade allow Salvaggio to continue tokenizing Black people.

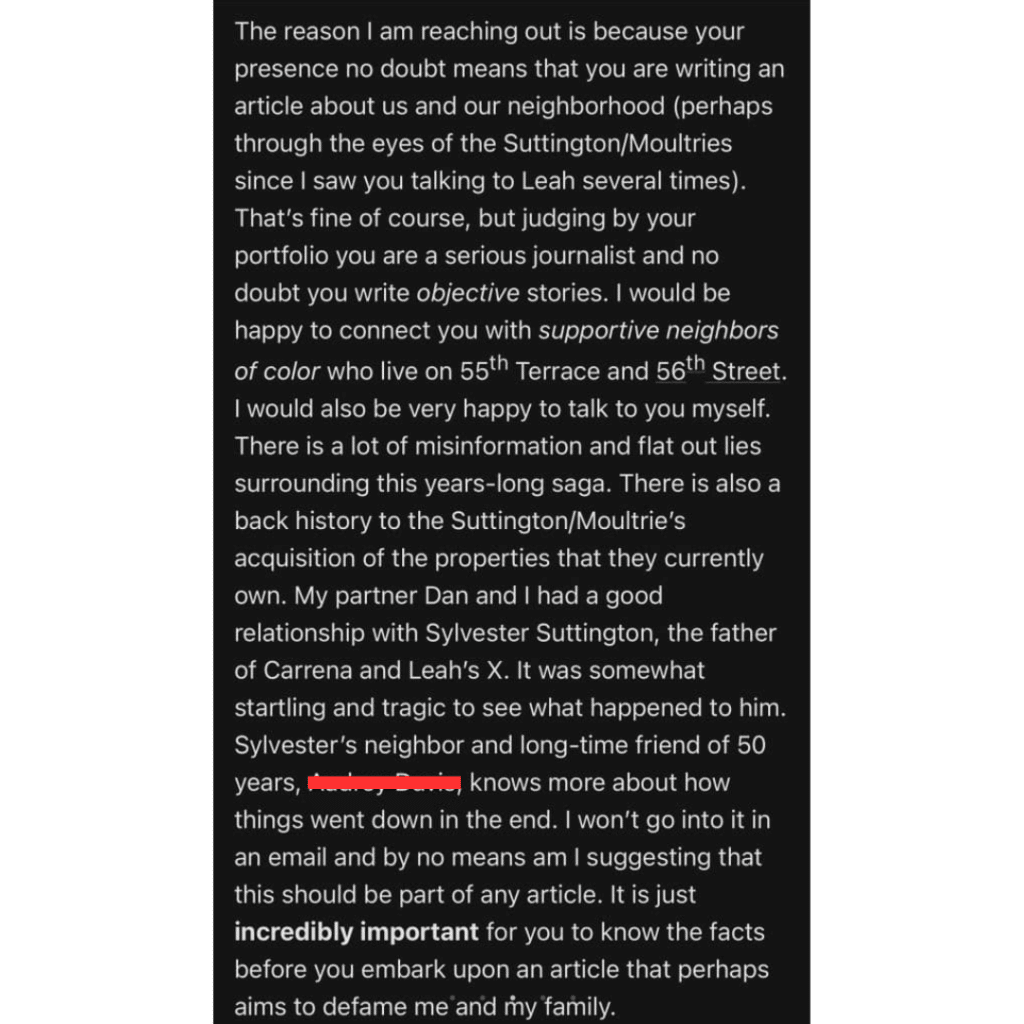

Last month, in an attempt to shift the open, yet quiet, narrative surrounding her character, Salvaggio emailed The Kansas City Defender. In that email, Salvaggio wrote, “I would be happy to connect you with supportive neighbors of color.” It was her attempt to use Black-led media to manipulate public perception in her favor.

Malcolm X said it best, “tokenism is hypocrisy,” and Salvaggio’s behavior is very hypocritical. She tokenizes Black people as part of her online persona to appear diverse and inclusive. It’s no different from conservatives who misinterpret and misapply Martin Luther King Jr. quotes. Tokenism reinforces power imbalances, undermines the experiences and contributions of Black individuals, and ultimately does more harm than good.

The ways in which Salvaggio weaponizes victimization and tokenism are strategic. In a campaign built on false victimhood, it reeks of performative activism.

In an op-ed penned to SWAAY, mental health advocate and author McKenna Kelley writes “Performative activism makes us question if people are actually changing their mindsets or simply appearing to do so.” In Salvaggio’s case, the latter applies. While Salvaggio may tote this “supportive neighbor of color” in her email communications, there are hardly any Black supporters or local Black farmers who side with Salvaggio on this matter publicly. In fact, even Salvaggio admits that 63% of their compost subscribers live in the 6th district — a district that sits west of the racial dividing line known as Troost Avenue and is historically white.

Author and gender and cultural studies professor A. Freya Thimsen defines performative activism as “a critical label that is applied to instances of shallow or self-serving support for social justice causes.” Salvaggio (and Heryer) use rally cries, slogans, picket signs, and organizing language as front for unspoken intentions that have detrimental impact.

Who Controls the Narrative in the Future of Urban Agriculture?

Perhaps the city council saw what I saw when I stepped foot into city hall at the Board of Zoning and Adjustment hearing earlier this year. I intended to tell a story of how a small business was misled by city officials. But upon seeing the stark difference in “supporters” and “opposers” it was clear that something more sinister was afoot. The unspoken racial divide on this saga rightfully became the focus. Salvaggio’s saving face antics demonstrated what many people were afraid to say on record.

Yes, composting is necessary. And regenerative farming practices are essential concepts that benefit everyone and the ecosystem. If implemented in a manner that respects the very concepts that inform regenerative agriculture, the impact that comes from it will be a testament to the legacy of afro-indigenous ancestors.

But if performative campaigns like “Save the Farm” are allowed to shape the future of urban agriculture moving forward, then we are setting a dangerous precedent that has proven time and time again to be most harmful to Black people.