The recent verdict in Sean “Diddy” Combs’ federal trial has shocked many. While the music mogul was found guilty on two counts of transporting women for prostitution, he was acquitted of racketeering and sex trafficking charges.

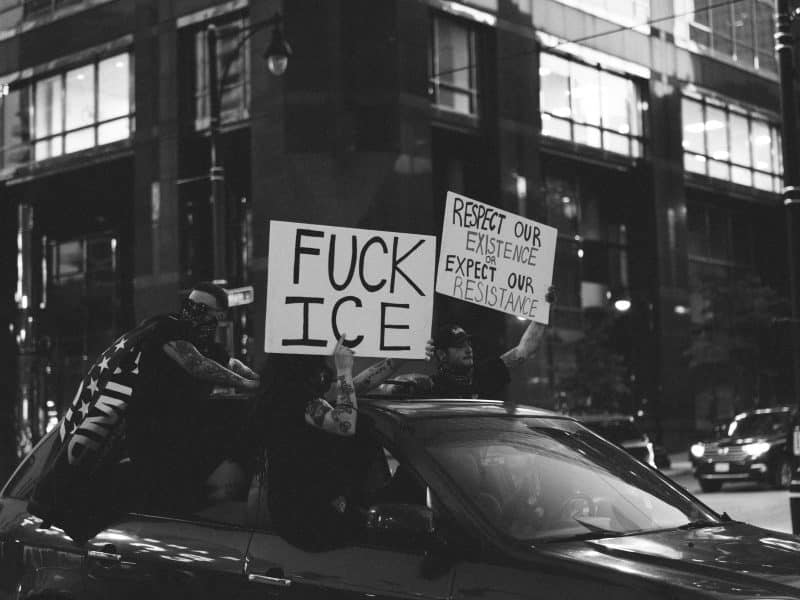

For many Black women, especially those in the entertainment industry, the ruling isn’t just a failure of accountability; it is a reminder of how rarely systems of power deliver justice, even when the evidence is overwhelming. The ruling also reinforced what many abolitionists already know: the court system was never designed to provide true justice for survivors. And for Black women, it can never be the ultimate path to justice.

Even with graphic evidence and public testimony, the legal system once again revealed its limits. But Combs is just the latest in a long line of powerful men whose abuse has been protected by status and silence.

This pattern is far from unique. Black women—famous or not—have long faced violence, disbelief, and dismissal. From surveillance footage of Combs dragging Cassie Ventura through a hotel hallway, to the shooting of Megan Thee Stallion by Tory Lanez, to the domestic violence experienced by Halle Bailey, Skai Jackson, and Keke Palmer, the response remains consistent: scrutiny of the survivor, protection of the abuser.

Celebrity Turmoil

Contrary to popular belief, celebrity status does not shield anyone from domestic violence and other forms of abuse by their partners. On the flip side, celebrities are not immune to having abusive tendencies, and oftentimes their fame can conceal their violence.

Let’s start with Sean Combs, also known as P. Diddy, or Diddy, among other aliases. In the past few years, the music mogul has attempted to turn his bad boy image around. He started doing philanthropic work and partnered with Bishop T.D. Jakes on a sermon in 2021 (Jakes would later be named in a lawsuit against the music mogul). In 2017, he announced a name change on social media, saying he wants to be called “Love” or “Brother Love.” But this “Brother Love” image would begin to crumble after Diddy’s ex-girlfriend, Cassie Ventura — the star witness in his federal trial — filed a lawsuit against him in November 2023, outlining a tumultuous, abusive relationship.

After Ventura filed her lawsuit, the floodgates opened. A slew of separate lawsuits were filed by various women and men, and Diddy was arrested and charged with racketeering conspiracy, two counts of sex trafficking, and two counts of transportation to engage in prostitution.

But in early July, Diddy was acquitted of all racketeering conspiracy and sex trafficking charges. One of his defense attorneys, Marc Agnifilo, called Ventura a “winner” for the $30 million settlement on her civil lawsuit back in 2023, but Ventura’s lawyer, Douglas Wigdor, responded in a statement saying that she was not a “winner” in 2023 or the day the final verdict was reached. ‘No amount of money’ would undo the abuse that she endured at the hands of Diddy, he said.

For the media, the main focus of the trial has been Ventura, who took the stand to testify about their 11-year relationship, one that was seemingly glamorous in the beginning but eventually became a nightmare full of coercion, control, and abuse. Barely a year before Diddy’s infamous name change, surveillance footage from a 2016 hotel incident—played in court—showed Combs dragging Ventura on the floor and kicking her. But the consequences of Diddy’s acquittal go far beyond monetary value and justice, or lack thereof, being served, and delve deeper into a cycle of abuse that Black women face.

In the midst of mounting allegations against Combs, Little Mermaid star, Halle Bailey, was granted a restraining order against rapper and streamer DDG, whose real name is Darryl Dwayne Granberry Jr. According to court filings, the order stemmed from an argument that turned violent in which DDG pulled Bailey’s hair and slammed her head against a steering wheel. Images of Bailey’s bruised arms and chipped front tooth made waves on social media in May after TMZ posted them. Messages between the former couple were also included in Bailey’s filing, with DDG accusing the actress of cheating on him with singer Brent Faiyez while she was on vacation in St. Lucia (Bailey later revealed she was there with her sister for Mother’s Day). A disturbing video of DDG talking aggressively to an AI-generated simulation of Bailey also went viral around the time news of the restraining order broke, further alarming fans and followers.

Days later, Skai Jackson, best known for her role as Zuri in Disney’s Jesse and Bunk’d, filed a restraining order against her child’s father, Deondre Burgin. In her petition she described Burgin punching her in the face, slamming her head against a car window while holding their newborn son Kasai, choking her, and even holding her at knifepoint while threatening to stab her in the stomach when she was pregnant. Burgin is ordered to stay 100 yards away from Jackson, their son, and her dog.

Another high-profile case of abuse involved actor and singer Keke Palmer, who had a very public dispute with her child’s father, Darius Jackson, after he tweeted his criticism of her outfit for Usher’s residency performance. Months later, Palmer filed and was granted a temporary restraining order after detailing multiple instances of physical abuse during their relationship.

Megan Thee Stallion has also faced an onslaught of insults and attacks on social media after speaking up about being shot by Tory Lanez in 2020. Her trauma has now resurfaced after Lanez’s attorneys recently claimed that there is “new” evidence suggesting that Tory was not the shooter, despite Lanez being tried, convicted, and sentenced for the shooting by the state of California.

Despite their celebrity status and star power, all these women have faced various forms of abuse from their former partners. These instances speak to a larger issue concerning our community and the need to protect Black women. Black women and our allies continue to call for action, but little is being done to rectify the abuse that is hurled at us, no matter how much we achieve or the amount of recognition we receive.

The Sad Reality for Black Women

The issue of domestic abuse is unique for Black women in a very devastating way. Black women and girls are more likely to face physical, psychological, and sexual abuse than any other racial group. Every four in 10 Black women have faced some kind of physical abuse from a partner in their lives, patterns which we have seen reflected in the case of Halle Bailey, Skai Jackson, Megan Thee Stallion, Keke Palmer, and Cassie Ventura.

To make matters worse, Black women are more likely to be killed at the hands of a man. According to a 2015 report from the Violence Policy Center, an overwhelming nine in 10 Black women knew their killers personally before tragedy struck. At the root of these tragic outcomes is misogynoir, a specific form of oppression where Black women face a “combination of racism and sexism.” Misogynoir plays the central role in this system that dehumanizes Black women and discredits our pain.

The Jezebel stereotype continues to follow Black women to this day, stemming from the days of slavery when white slave masters categorized Black women as not just property, but labeling them as “promiscuous” to justify raping them. Systemic racism classifies sex as the “‘natural’ role” for Black women and girls, focusing only on our bodies, what they can do, and the pleasure our bodies can offer others. This stereotype has also led to the adultification of young Black girls in our community, with them being called “fast” just for growing up and exploring themselves as people. From the moment she is born, a young black girl’s innocence is forfeited, and she’s left unprotected before she even hits puberty.

Why It’s Hard to Speak Up and How to Create Space

In instances of domestic abuse, people always wonder why survivors don’t simply leave their abusers. But this notion is deeply harmful and leads to victim-blaming, pushing survivors into an already tight corner. There are several reasons survivors don’t just up and leave, which could include finances, children being involved, and the abuser threatening to harm the victim or those close to them.

Power dynamics and age also shape the conditions of abuse. In Cassie and Diddy’s case, Diddy is 17 years older than Cassie, making him about 36 years old when he started dating Cassie, who was 19 when they met. Their nearly two-decade age gap is disgusting on its own, but the imbalance was compounded by Diddy’s status as an established music mogul, while Cassie was just starting out in her singing career. The disparity in life experience, career power, and public influence made it even harder for her to navigate, resist, or escape the abuse she endured.

Now, in the wake of Diddy’s acquittal on federal sex trafficking charges, we’re once again reminded how the legal system fails to recognize and respond to the realities survivors face, especially Black women. According to a federal statute, sex trafficking or human trafficking includes “compelling or coercing a person to provide labor or services, or to engage in commercial sex acts.” Yet to the public, trafficking is often misunderstood — seen only as kidnapping or force, not coercion, manipulation, or control.

The video played in court showed Diddy’s violent reaction to Ventura’s refusal to participate in a “freak-off” session. Even in her civil lawsuit, she described feeling like she couldn’t refuse Diddy’s demands for drugs and sex, fearing the consequences if she did. These accounts make it clear that Ventura did not feel safe or free to say no, meaning her participation was never truly consensual. And yet the court, made up of a jury of Diddy’s “peers,” refused to see it that way.

These abuses experienced by these celebrity Black women aren’t isolated; they are happening within and throughout our community.

It’s time to make a change.

In a celebrity culture that feeds us dreams of success and glamor, we have seen what happens when Black women speak up about their abuse: we are dismissed, discredited, or blamed. Society demands that survivors of abuse tell their stories, only to be met with questions such as “Why didn’t you report this sooner?” or “Why did you stay for so long?”

And even when overwhelming evidence is made public and proven in court beyond a reasonable doubt, survivors are still ridiculed and mocked online, re-traumatized by viral posts, and forced to watch as their abuses are defended with hashtags like #Free(insert name).

This dynamic plays out regardless of how a Black woman is perceived by the public. Consider the contrast between Halle Bailey and Megan Thee Stallion. Bailey is seen through a “good girl” lens and has a socially acceptable image, while Megan is viewed as hypersexual. Yet they were both discredited in the realm of social media for speaking up about their abuse. The message is clear: even when Black women do everything “right,” we’re still not believed.

But something has to give. Black women cannot continue yelling into an empty void. It is time to truly listen— to make space for Black women and girls to be vulnerable, heard, and protected. It’s time for us as a society to ask how abuse can be rectified, instead of piling on another issue for only Black women to address. The responsibility belongs to all of us.

ABOUT DEFENDER EDITORIALS

This article is part of The Defender Editorial Series, our official opinion section.

At The Kansas City Defender, we distinguish between reporting and editorial writing:

- Our reporting is rooted in data, documentation, and on-the-ground sourcing. It exposes injustice, centers Black voices, and holds power accountable.

- Our editorials and opinion columns are explicitly framed pieces. They go beyond the what/where/when to offer cultural context, political analysis, and movement-grounded perspective. They’re written not from above or outside—but from within our communities, our struggles, and our visions for liberation.

We proudly acknowledge that our editorial and opinion writers are often the same people who report our stories. We believe there is no contradiction between rigorous journalism and unapologetic moral clarity.

We are not neutral. We are with the people.