There is a particular kind of audacity that reveals itself when a man, caught in the gears of his own choices, decides to blame Black people rather than admit he walked into a perilous situation with both eyes open.

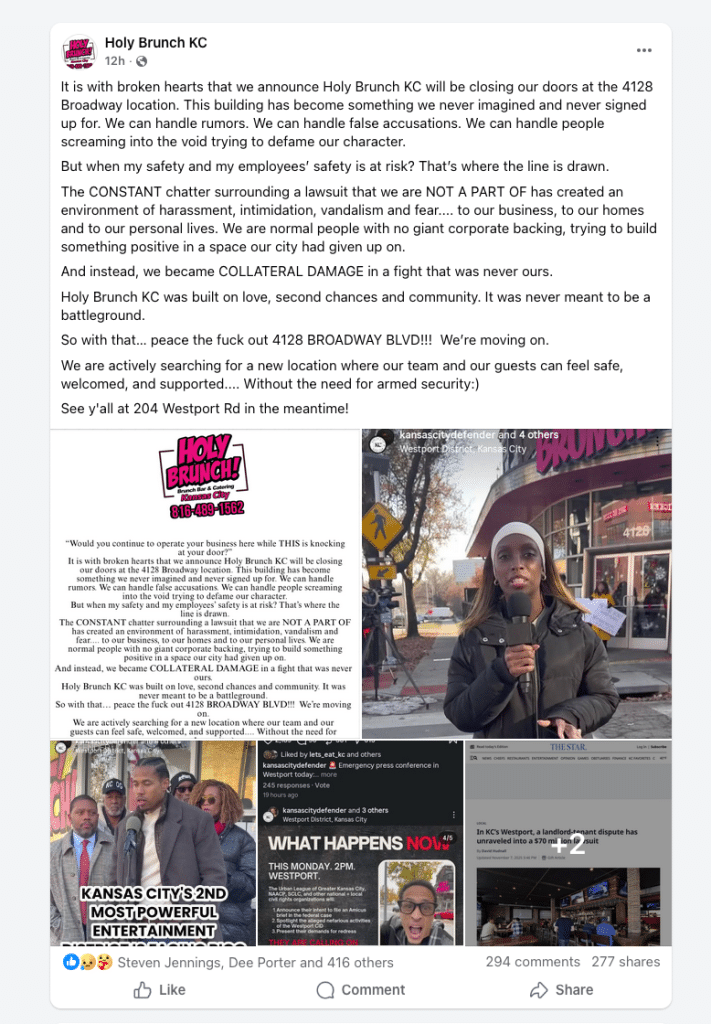

On Wednesday December 10th, Andrue Stewart, owner of Holy Brunch KC, announced the closure of his 4128 Broadway location with all the theatrical grief of someone who had been wronged by forces beyond his comprehension. “This building has become something we never imagined and never signed up for,” he wrote in a Facebook post that has since ricocheted across Kansas City’s social media landscape.

“We never imagined.” “Never signed up for.”

These are interesting words. They are also, to put it plainly, lies.

For Those Just Tuning In

If you have not been following this case, here is what you need to know:

In January 2025, Euphoric, LLC, owned by Black restaurateur Christopher Lee, filed a federal RICO lawsuit against the all-white Westport Community Improvement District (a small group of powerful individuals who control what businesses do and don’t get to open in Westport) and the owners of 4128 Broadway, the building Holy Brunch currently occupies.

In a validation of the case’s credibility, U.S. District Judge Roseann Ketchmark allowed the RICO charges to proceed. RICO claims are among the most difficult to sustain in federal court, typically reserved for organized crime and large-scale fraud. The fact that this case survived means a federal judge found the allegations of a coordinated, racially discriminatory enterprise plausible enough to merit trial.

The lawsuit alleges a pattern of racial discrimination designed to exclude Black business owners from one of Kansas City’s most profitable entertainment districts.

The explosive allegations include a secret “No Play List” that banned Black music such as Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar, and Drake from Westport venues. “Good Neighbor Agreements” that plaintiffs describe as racially coded legalized extortion, used to control which businesses could operate and which would be forced out. A coordinated effort to deny Black entrepreneurs access to liquor licenses, leases, and economic opportunity.

Christopher Lee signed a lease for 4128 Broadway. He paid a $10,000 deposit. When it was time for him to move in, the Westport CID refused to give him the keys (even though he already paid the $10k deposit). Shortly after, the white owners of Holy Brunch were quickly permitted to proceed in opening their business at the location in dispute.

All of this is documented with receipts in the excellent investigative reporting published by my colleague JT Taylor in his earlier piece titled “Federal RICO Case Alleges an All-White Board Runs Westport Nightlife Like a Racist Cartel,” which I highly recommend giving a read.

This led to the most recent incident this week, December 8, 2025, where national civil rights organizations, including the Urban League, the NAACP, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, held a press conference in Westport announcing their intent to file an amicus brief in the case. That press conference was held in front of 4128 Broadway, although no organizers ever mentioned or criticized Holy Brunch in any way.

Two days later, Andrue Stewart announced he was closing that location and blamed the Black civil rights leaders and Black entrepreneurs for his troubles.

This is where we pick up the story.

Court Evidence Transcript Reveals Stewart’s Knowledge of Ongoing Legal Dispute Prior to Opening Business

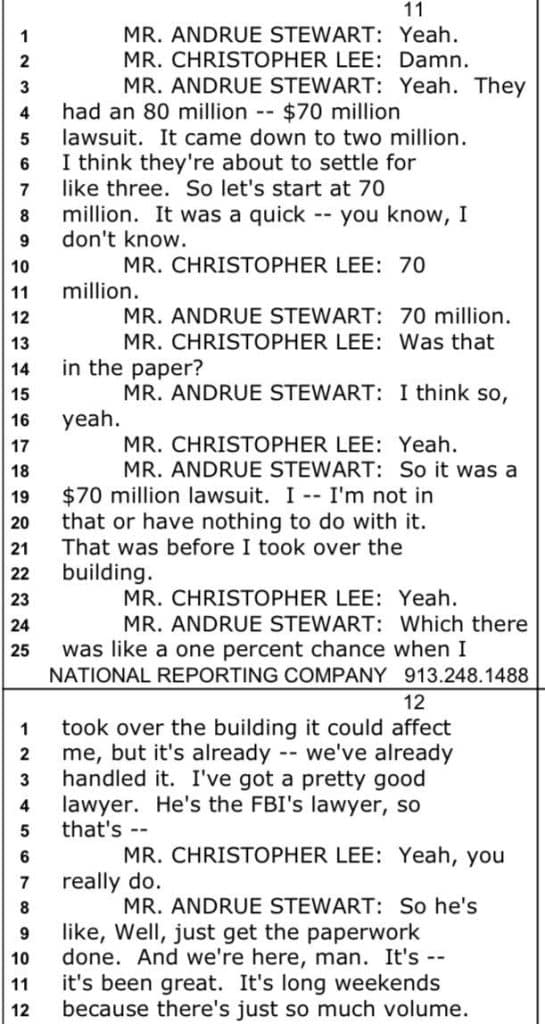

What Mr. Stewart perhaps forgot, in his rush to cast himself as “collateral damage” in a fight that was “never ours,” is that his own words have been transcribed, submitted to federal court, and entered into evidence.

“Andrue Stewart, owner of Holy Brunch, knew the building was disputed in a discrimination suit and still chose to lease this space and even consulted an attorney to do so,” civil rights attorney Cecilia J. Brown who is representing the plaintiffs in the lawsuit told me in a statement. “No one in the civil rights community has done anything to hurt their business. Holy Brunch must take accountability for its bad business choice.”

In the aforementioned recording which has been submitted as evidence to the court, made during a conversation between Stewart, Christopher Lee (the Black restaurateur at the center of the Westport RICO case), and a woman named Kaitlyn Vansel, Stewart is revealed as a man who knew exactly what he was walking into.

The conversation begins with Vansel mentioning she had seen something in the news about the building:

MS. KAITLYN VANSEL: Yeah, because I thought I saw something in the paper, I was like, I didn’t know what they were going to turn this place into, so…

MR. ANDRUE STEWART: So KCMO, there was 11 people trying to rent it before me. They turned them down because they had nightclub vibes. They didn’t want a nightclub in here because of the shootings and all the crazy shit that always happened outside.

MS. KAITLYN VANSEL: It got bad like that?

MR. ANDRUE STEWART: It got bad. Stabbings, shootings… Overdoses from coke. It got real bad here.

Then Christopher Lee asks the question directly:

MR. CHRISTOPHER LEE: Is this the place that was in the paper, like…

MR. ANDRUE STEWART: Yeah.

MR. CHRISTOPHER LEE: Damn.

MR. ANDRUE STEWART: Yeah. They had an 80 million… $70 million lawsuit. It came down to two million. I think they’re about to settle for like three. So let’s start at 70 million.

MR. CHRISTOPHER LEE: 70 million?

MR. ANDRUE STEWART: 70 million.

MR. CHRISTOPHER LEE: Was that in the paper?

MR. ANDRUE STEWART: Yeah.

Let us pause here. Mr. Stewart is casually discussing, in granular detail, a $70 million lawsuit attached to the very building he chose to lease. He is not learning about this for the first time. He is recounting it like someone who has done his homework.

The conversation continues:

MR. ANDRUE STEWART: So it was a $70 million lawsuit. I’m not in that or have nothing to do with it. That was before I took over the building.

MR. CHRISTOPHER LEE: Yeah.

MR. ANDRUE STEWART: Which there was like a one percent chance when I took over the building it could affect me, but it’s already… we’ve already handled it. I’ve got a pretty good lawyer. He’s the FBI’s lawyer, so that’s…

MR. CHRISTOPHER LEE: Yeah, you really do.

MR. ANDRUE STEWART: So he’s like, Well, just get the paperwork done. And we’re here, man…

Let us be precise about what this exchange reveals:

Mr. Stewart knew about the lawsuit before he signed. He knew the dollar figures. He knew eleven other potential tenants had been turned away. He consulted an attorney, one he brags is “the FBI’s lawyer.” That attorney assessed the situation and advised him to “just get the paperwork done.” Stewart calculated the risk at “one percent” and decided the gamble was worth taking.

He signed the lease anyway.

And now, when that one percent has come calling, he writes on Facebook: “This building has become something we never imagined and never signed up for.”

Sir, respectfully: the transcript says otherwise. You imagined it. You assessed it. You lawyered up for it. You signed up for it anyway.

The tape does not lie.

But perhaps what is most instructive about Mr. Stewart’s lament is not what it contains, but what it omits.

In his lengthy post decrying “false accusations” and “harassment,” Mr. Stewart managed to avoid a rather glaring question: Does he believe the allegations against the Westport CID are credible? Does he think Black business owners have been systematically excluded from one of Kansas City’s most profitable entertainment districts? Does he have any opinion whatsoever on the “No Play List” that banned Beyoncé, Kendrick Lamar, and Drake from being played at Westport venues? On the secret “Good Neighbor Agreements” that plaintiffs allege as extortion dressed in the language of community stewardship?

He does not say. He offers no condemnation of the alleged racist cartel that controlled who could and could not open businesses in Westport. He expresses no solidarity with the Black entrepreneurs who, unlike him, were never given the keys to begin with.

Instead, he points his finger at a Black media platform, a Black woman, Black civil rights leaders and Black entrepreneurs.

The Attacks on Black Media

In his post, Mr. Stewart included screenshots of our coverage. Our social media posts. A photograph of our reporter, Tiffany, a Black woman whose only “crime” was showing up to document a press conference organized by the Urban League-KC, the NAACP-MO, SCLC-KC, and the Urban Council. Organizations that have been fighting for civil rights since before Mr. Stewart’s restaurant began serving pumpkin pancake tacos.

Let us be clear about what The Defender did and did not do.

We reported on a federal RICO lawsuit that alleges a pattern of racial discrimination in Westport’s business community. We covered a press conference held by nationally recognized civil rights organizations, which took place in front of Holy Brunch because that particular building is implicated in the ongoing legal dispute. We published photographs of a building that is a matter of public record in federal court filings.

We never targeted Holy Brunch in any of our articles or coverage. We never accused Mr. Stewart of wrongdoing. We never called for boycotts, protests, or any action against his establishment.

What we did was journalism. What Mr. Stewart did was screenshot a Black woman doing her job and post it to Facebook as if she were somehow responsible for his business decisions.

There is a word for blaming Black media and Black reporters for the consequences of your own choices. Several words, actually. None of them flattering.

And here is what makes Mr. Stewart’s selective outrage so revealing: The Kansas City Defender was not the only outlet to feature Holy Brunch in coverage of this case. FOX4 News aired footage of the building with the chyron “Urban Council to Condemn” visible beneath the Holy Brunch sign.

KMBC broadcast live from Westport with “Lawsuit Launched Against District” displayed while the Holy Brunch logo filled the screen.

Thousands of Kansas Citians saw that building on their televisions, courtesy of major network affiliates.

And yet.

Mr. Stewart did not screenshot FOX4. He did not accuse KMBC of harassment. He did not post photographs of their reporters and insinuate they were responsible for his closure.

He reserved that treatment for The Kansas City Defender. For Tiffany. For Black media.

One might wonder why.

What “Never Signed Up For” Actually Means

What Mr. Stewart actually signed up for is a building with a complicated history. A lease clouded by ongoing litigation. A location that was, by his own admission, rejected by eleven other potential tenants before him. A space where, again by his own words on tape, “stabbings, shootings” and “overdoses from coke” had occurred. A one percent chance that the legal mess might touch him.

Missouri law has a term for this, it is caveat emptor, meaning “let the buyer beware.”

Mr. Stewart was warned. By his lawyer and by his intimate knowledge of the controversy surrounding the building as well as the existence of the major pending lawsuit.

He was not blindsided or caught unaware. He made a calculated decision that the controversy would pass, that the lawsuit would settle, that he could build his brunch empire on a foundation of someone else’s injustice.

The foundation shifted, but that is not The Defender’s fault, just as it is not Christopher’s fault or the fault of the Urban League, the NAACP, or any civil rights leader advocating in this case.

That is the fault of a man who bet on one percent and lost.

Yet, there was a kernel of truth in his explicative-filled Facebook post. Which is, that there was indeed collateral damage in this story. However, the victim of that collateral damage is not Andrue Stewart.

It is people like Christopher Lee, who did everything right, signed a lease, paid his deposit, generated buzz for his business, and was allegedly told to “sue me” by a landlord who admitted on tape there was no breach.

It is DJ Street King, who (like many other Black promoters and DJ’s) alleges he was blacklisted from Westport venues because a CID board member threatened to pull liquor licenses from any bar that hired him.

It is every Black entrepreneur who looked at Westport and saw opportunity, only to be told, through secret agreements and coded language about “the wrong crowd” and “young hip-hop vibes,” that they were not welcome.

It is the community of Steptoe, one of Kansas City’s first Black settlements, which once stood where Westport now serves mimosa towers, and which was systematically erased to make room for the very district that now excludes Black business owners.

That is collateral damage. A brunch restaurant closing one of its two locations because its owner made a bad bet? That is a business decision.

The Weaponization of White Tears, White Victimhood & the Demonization of Black People

Andrue Stewart had every opportunity to be an ally. He could have acknowledged the troubling history of the building he leased or expressed support for Black entrepreneurs who have been shut out of Westport. He could have used his platform to call for transparency and accountability from the CID or even, at minimum, remained silent and let the legal process unfold without casting himself as the victim.

Instead, he chose to screenshot a Black woman, blame Black media, and perform the kind of wounded innocence that only works when no one has access to the transcript.

But we have the transcript. And in the transcript, Mr. Stewart says he knew about the lawsuit. He consulted a lawyer. He assessed the risk. He proceeded anyway.

“This building has become something we never imagined and never signed up for.”

The tape says otherwise, Mr. Stewart. The tape says otherwise.

The Kansas City Defender will continue to cover the Westport RICO case as it proceeds through federal court. We remain committed to investigative journalism that centers the voices and experiences of Black Kansas Citians, regardless of who finds that coverage inconvenient.

Got tips or testimony related to discrimination in Kansas City? Contact me securely at ryan@kcdefender.com.