THE DEFENDER HANDBOOK

Radical Roots

& Social-First

Digital Tactics

01.

Reporting on Policing

& Public Safety

This guide provides key principles for journalists to critically engage with abolitionist reporting. It emphasizes resisting police narratives and using thoughtful language to promote a just discourse in community safety

How-To: Be An Abolitionist Reporter

The Defender’s Abolitionist Writer’s Guide

We are very intentional about the way we cover cops, “crime” and state violence. Our editorial decision-making in this realm is largely informed by our Abolitionist Writer’s Guide and tools like the “Don’t Be a Copagandist” media resource compiled by Mia Henry, Lewis Raven Wallace, and Andrea J. Ritchie, as well as the scholarship of Alec Karakatsanis.

Alec Karakatsanis

“Copaganda describes a special kind of propaganda, perpetuated by the police and media, that affects who and what we fear and what kinds of social investments we support to address our fears.”

Don’t Be a Public Relations Agent for Police

The Defender’s Abolitionist Writer’s Guide

Police already have massive public relations operations within their departments, such as LA County who has over 67 cops dedicated solely to PR/Information operations.

Many journalists, whether knowing or unknowing, partake in public relations on behalf of cops — either by unquestioningly parroting police reports and/or by utilizing police language and narratives. By doing so you are actively perpetuating state violence against oppressed communities. Presenting police narratives without doing further investigating and fact-checking further enacts the violence of the police state, especially in situations like shootings by police, where cops are central participants in the story.

An “Official Police Report”

is Not a Singular

Objective Truth

In many cases, it is not the truth at all and instead serves as what can be described as “state-sanctioned disinformation.”

Police-Steered Narratives

Leaves No Room

for Other Accounts

Whose side is not being told? What is the community saying? We consider community voices as authoritative, and in most cases hesitate to believe police narratives without further independent verification.

Journalists are

Taught Not to Rely

on a Single Source

Journalists should be skeptical of all information presented, yet often ignore this rule when reporting on cops and thus actively perpetuate state violence against oppressed communities.

One clear example is the police report following the death of George Floyd which made no mention of the fact he was strangled by a cop for eight minutes. The police report headline reads, “Man Dies after Medical Incident During Police Interaction,” while the body of the report reads “He was ordered to step from his car. After he got out, he physically resisted officers. Officers were able to get the suspect into handcuffs and noted he appeared to be suffering medical distress. Officers called for an ambulance. He was transported to Hennepin County Medical Center by ambulance where he died a short time later.”

Source: Investigative Update on Critical Incident – Web Archive

The police report following Floyd’s lynching explicitly concealed his murder, criminalized him, and exonerated killer Derek Chauvin of any wrongdoing. Police reports serve as fabricated evidence, creating an alternate reality that is disseminated to media outlets as an objective account. Due to time constraints and demand for stories, outlets often accept them as fact.

In these situations, media outlets often operate as police public relations agents. Reporters used the common “police say” headline, where they present a framing, story, or allegation, and rely solely on the word of cops.

Josmar Trujillo

“It’s not just an example of when police are overly quoted in a story, or used as the only source in the story, or when there is favorable coverage or bias given to them. The stories are the symptoms. The core of copaganda is that symbiotic relationship between the press and police. Police rely on press and press rely on police.”

Use of Language

The Defender’s Abolitionist Writer’s Guide

In our work, we don’t use passive language and police terminology that remove the implication of guilt or disguise power dynamics. Examples include phrases like “officer-involved shooting,” “man dead after struck by a bullet after police confrontation,” or “a struggle ensued.”

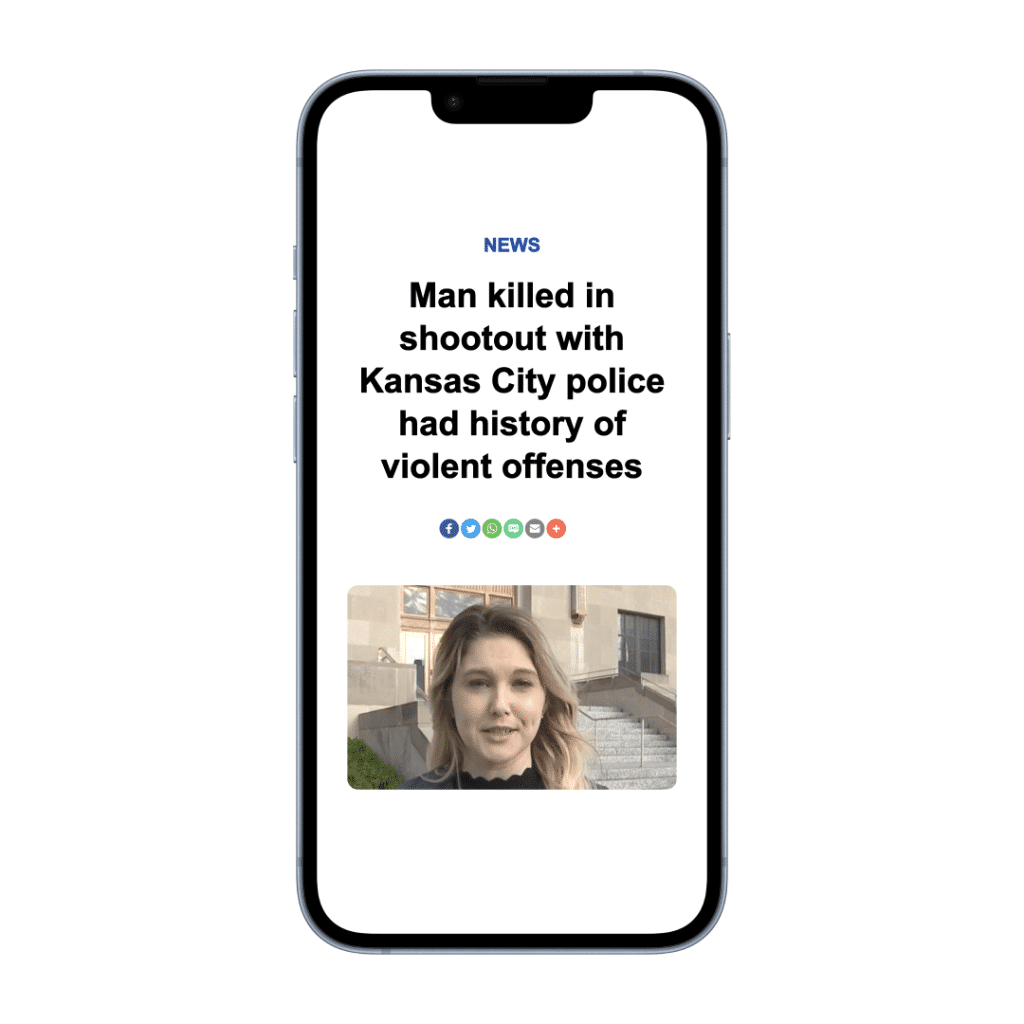

Criminalizing Headlines

- Misleading Causality: Johnson wasn’t killed in a shootout; he was killed by police.

- Criminalizing Context: Bringing up Johnson’s history of violent offenses attempts to justify his murder by portraying him as an aggressor.

- Dehumanization: Referring to Malcolm Johnson as “man” strips him of his identity and humanity.

Those following the story later learned that not only was Johnson not wielding a weapon, he was actually being pinned down by 3-4 cops when one cop executed him by shooting him in the head from point-blank range.

Criminalizing Headlines

- A prime example of cops exploiting their relationship with the media to circulate State-Sanctioned Disinformation.

In this same tragedy, a different local media outlet further dehumanizes and criminalizes Johnson as a “slain suspect,” i.e. not a human deserving of empathy. Even further, video of the murder would reveal that what was alleged to be a “shootout” involving Johnson, was actually one cop who accidentally shot the other before shooting Johnson in the head from point blank range.

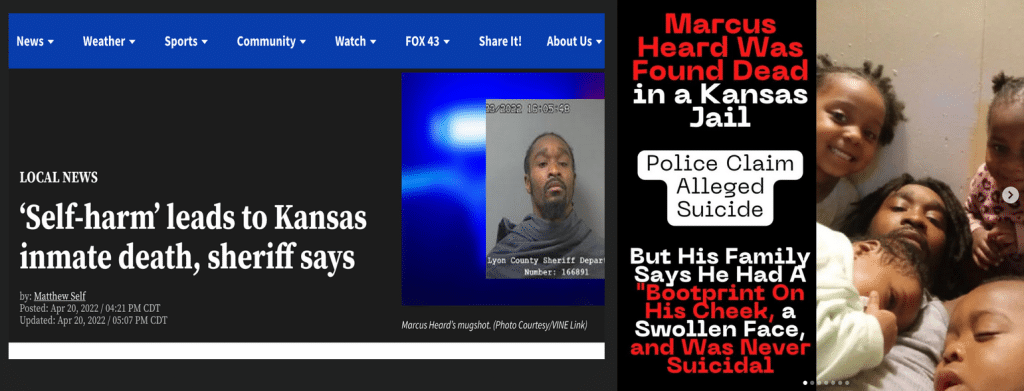

In a separate story we covered in the example below, notice how legacy media refers to “self-harm” as a prime cause of unexplained death, with the only source being a sheriff’s (the state/authorities) account. To create actually balanced reporting, our piece flips the typical assumption of authority and refers to the cops’ claim as an “allegation” while contextualizing the events with the perspective of Marcus Heard’s family.

Employing passive language to absolve guilt isn’t only used in Copaganda. Similar problematic and even intentionally deceitful language is consistently used by mainstream media when covering the genocide and horrifying massacres of Palestinians.

With the headline, “Hundreds Reported Killed in Blast at a Gaza Hospital,” no actor is named, though the subhead mentions “people” seeking shelter from israeli bombings. The headline’s refusal to name Palestinians as the victims of an israeli bombing results in an abstracted statistic instead of an unspeakable tragedy. Euphemistic language is often used to soften, obscure and erase the severity of atrocities inflicted on oppressed groups.

Alec Karakatsanis

“Police want us to focus on crimes committed by the poorest, most vulnerable people in our society and not on bigger threats to our safety caused by people with power. For example, wage theft by employers dwarfs all other property crime combined — from burglaries, to retail theft, to robberies — costing an estimated $50 billion every year. Tax evasion steals about $1 trillion each year.

That’s over 60 times all the wealth lost in all FBI reported property crime combined in the entire U.S. There are hundreds of thousands of Clean Water Act violations each year, causing cancer, kidney failure, rotting teeth, and damage to the nervous system. Over 100,000 people in the United States die every year from air pollution, five times the number of all homicides.”

Question Police Statistics

Here is a comprehensive overview of how police statistics can be misleading or serve as disinformation:

Selective Reporting

Focusing on certain crimes to shape public perception or justify funding and resources.

Non-Crime Harms

Excluding systemic harms like housing insecurity, healthcare neglect, and educational inequities from discussions on public safety.

Lack of Context

Presenting statistics without context, such as historical crime trends, socioeconomic factors, or community impact.

Impact of Policing Practices

The influence of policing practices on crime rates, where increased policing might not correlate with actual reductions in crime but rather in increased arrests for minor infractions.

Data Collection and Reporting Biases

Focusing on certain crimes to shape public perception or justify funding and resources.

Definition and Classification Changes

Altering how crimes are defined or classified to artificially lower crime rates.

Underreporting of Police Misconduct

Failing to include instances of police brutality or misconduct in crime statistics. Community members may also not report incidents due to distrust of or fear of the police.

Overemphasis on Violent Crime

Highlighting violent crime rates while ignoring or minimizing systemic issues like wage theft, environmental hazards, and other forms of systemic violence.

Guidelines for Reporting on Violence

By adopting these guidelines, newsrooms can contribute to a more informed and nuanced discussion about public safety, violence, and the role of policing in society, moving towards reporting that empowers communities and fosters a deeper understanding of systemic issues.

Avoid Equating Violence Solely with Crime

Understand that violence takes many forms, including houselessness, extreme poverty, systemic racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination that may not be criminalized but are deeply harmful. While something like marijuana possession is categorized as a “crime” and has caused decades of incarceration for millions of Black people, it generally causes less harm than other legal substances like alcohol or cigarettes.

Reject “If it Bleeds It Leads” Mentality in Covering Violent Events

Avoid reporting on every shooting or violent act simply for the sake of covering it.

What is the reason you are covering it?

What do you want the community to take away from the coverage?

The unfortunate reality is that violence is prevalent in our cities, and continuous coverage of every violent act—while neglecting other happenings in our community—contributes to a heightened sense of fear and a distorted perception of the prevalence of violence.

Read the full “Reporting on Violence Tip Sheet.”

Avoid Sensationalism

Sensationalizing violent incidents can amplify fear and may lead to reactionary public and policy responses that do not address root causes.

Avoid Isolating Acts of Violence

Connect incidents of violence to broader systemic issues rather than treating them as isolated events. This approach helps to highlight root causes and potential systemic solutions.

Avoid Unquestioned Reproduction of Police Narratives

Be critical of law enforcement’s portrayal of events and statistics, which are often aimed at shaping public opinion to support increased policing and surveillance.

Avoid Ignoring the Impact of Police Violence

Reporting on violence should include consideration of violence perpetrated by law enforcement, recognizing its impact on communities.

Avoid Dehumanizing Language

Use language that respects the humanity of all individuals involved, avoiding terms that may stigmatize or dehumanize.

Don’t Overlook Community-Led Solutions

Highlight and explore community-led initiatives and solutions to public safety concerns, rather than defaulting to police-centric responses.

Don’t Ignore Historical Context

Recognize and incorporate the historical context of policing and criminal justice issues, especially as they relate to Black communities and other marginalized groups.

Avoid Simplistic Solutions to Complex Problems

Acknowledge the complexity of violence and public safety issues, resisting the urge to present policing as the sole or primary solution.

Acknowledge Structural Violence

Recognize and report on structural violence such as housing insecurity, food deserts (areas that have no fresh food grocery stores), healthcare disparities, and educational inequities as forms of violence that deeply impact communities.

Criminalizing Language: A Terms Guide

We warn against using dehumanizing police terminology and stereotypes, especially regarding race and socioeconomic status. This list reflects a commitment to humanizing individuals and challenging systemic injustices:

Don’t use “Offender” / “Criminal”

Use “person convicted of a crime” or “person who has been incarcerated” to focus on the individual beyond their legal situation.

Don’t use “Inmate” / “Convict”

Use “person who is incarcerated” or “person in prison/jail” to emphasize their humanity first.

Don’t use “Detainee”

Opt for “person in detention” to avoid depersonalizing language.

Don’t use “Ex-con” / “Ex-offender”

Use “formerly incarcerated person” to acknowledge their humanity beyond incarceration.

Don’t use “Crime”

Use “harm” to emphasize the impact on individuals and communities rather than the legalistic term “crime,” which lacks nuance, has racist connotations and ignores systemic factors. If it is necessary to use “crime” provide context and explain why.

Don’t use “Criminal Justice System”

Replace with “criminal punishment system” or “criminal legal system” to highlight the system’s focus on punishment rather than justice or rehabilitation. The existing carceral system does not produce “justice.”

Don’t use “Suspect“

Instead consider phrases like “person accused by police” to maintain the presumption of innocence and avoid prejudging the individual based on police allegations.

Don’t use “Violent vs. Non-Violent Crimes”

Be cautious with these labels, which can oversimplify complex situations and reinforce harmful stereotypes. Focus instead on the specifics of the harm caused and the circumstances around it.

Mugshot Marginalization

The Defender’s Abolitionist Writer’s Guide

We almost never publish mugshots, as they perpetuate criminalization and stereotypes, causing irreparable harm to individuals’ reputations. This affects their opportunities for employment, housing, and social integration long after their encounter with the justice system.

This practice can reinforce a cycle of stigma and marginalization, counteracting our mission to report with integrity and compassion.

According to an intensive Equal Justice Initiative study of 10 criminal cases (five with a Black defendant and five with a white one):

4x

White victims were nearly 4x more likely to be presented in photos with friends and family than Black people victimized by crime.

45%

Mugshots were used in coverage of 45% of cases involving Black people accused of crimes compared to only 9% of cases involving white defendants.

50%

Media coverage was 50% more likely to refer to white defendants by name as compared to Black defendants.

Skepticism of Police “Solutions”

Do not simply repeat police-proposed solutions to violence, such as increased surveillance or technology, which are scientifically proven to be ineffective. For example, a 2022 Department of Justice publication declares “a comprehensive review of 70 studies of body-worn cameras use…showed no consistent or no statistically significant effects.” Do research, engage in your own education on demands organizers put forth, and conduct additional interviews and reporting to seek out less harmful and more effective solutions.

This infographic created by Critical Resistance, a PIC Abolitionist organization, outlines various solutions that align and do not align with our Abolitionist values.

Checklist for Respecting Privacy in Solidarity Reporting

Stress the importance of respecting names, pronouns, and requests for anonymity, especially concerning vulnerable groups.

☑️ Prioritize Consent and Pronoun Respect

Obtain explicit consent before sharing personal stories or information. Ask individuals for their pronouns and respect their identities.

☑️ Understand Historical and Ongoing Trauma

Be aware of the trauma being experienced especially in Black communities and approach each interaction with sensitivity.

☑️ Be Willing to Provide Anonymity

Evaluate the potential impact on privacy. Offer anonymity to protect individuals from harm, especially when discussing sensitive issues.

☑️ Verify and Protect Information

Ensure the accuracy and necessity of personal information shared, and implement strong data protection measures.

☑️ Transparent Reporting Process

Clearly communicate how information will be used, where it will be shared, and who will have access to it.

☑️ Mindful Sharing with a Focus on Safety

Consider the broader implications of sharing stories, prioritizing the safety and privacy of those featured.

☑️ Feedback Loop for Community Voice

Create mechanisms for feedback on reporting, addressing concerns about privacy and representation.

☑️ Approach Families Impacted by Violence as Community

When engaging with families affected by violence, do so as a community member, offering support and solidarity rather than approaching from a detached or extractive perspective.

KC x RJI Partnership

Support Radical

Black Press

The Kansas City Defender and the Reynolds Journalism Institute are proud to partner in creating a toolkit that will include the rich history of the radical Black press, its vital contributions to the future of the field, and a template for a media landscape that genuinely caters to the needs of our communities.