You’ve felt it before, even if you didn’t know what to call it.

The bench at the bus stop with the armrest jutting up in the middle, making sure nobody can stretch out when they’re bone-tired after a double shift. The bumps and ridges embedded in the concrete where people used to sit. The bus stop benches that simply disappeared all across Kansas City one day where folks gathered, leaving them to wait with nowhere to rest and nowhere to shelter.

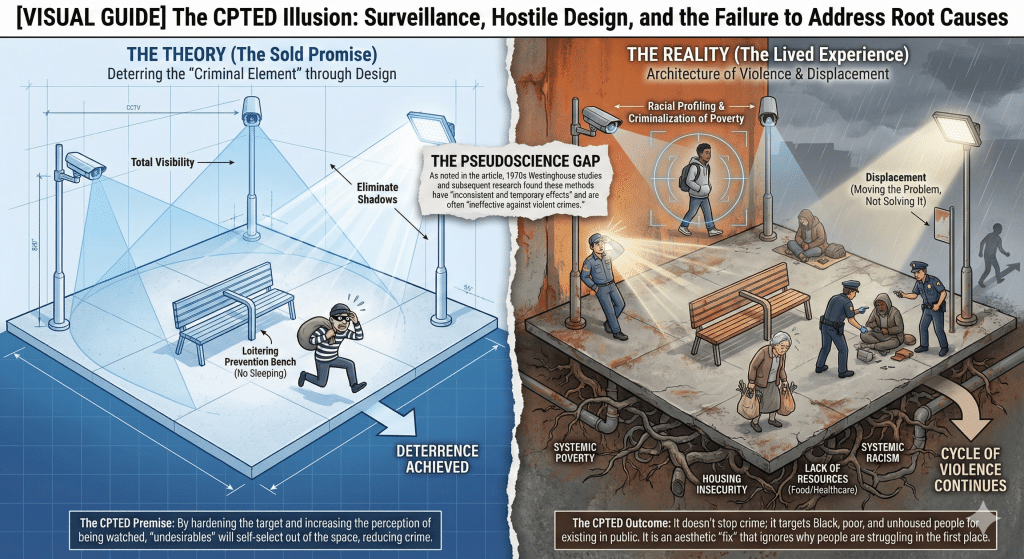

You probably thought it was just terrible design. While that is indeed the case, it’s also something more. It’s called Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) and it was created specifically to keep Black folks, poor folks, and unhoused folks out.

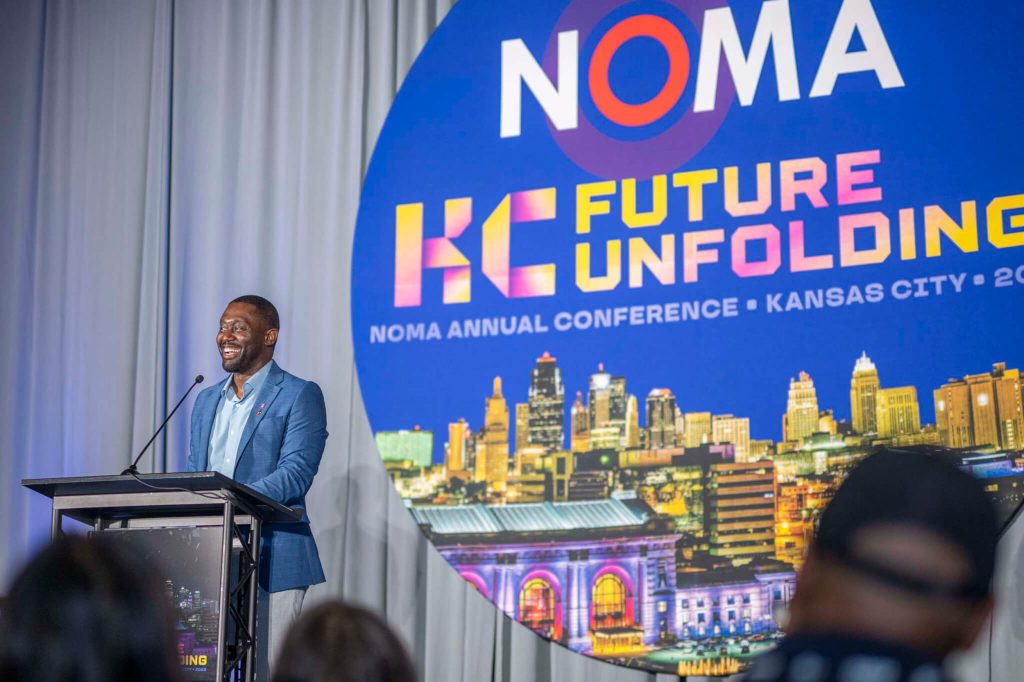

“What I found in the research early on was that almost none of that worked,” Bryan C. Lee Jr., President of the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA), tells me over breakfast during the NOMA 2025 conference in Kansas City. We’re at a table where he’s ordering breakfast, his energy both exhausted and electric after days of conference programming.

In the 1970s, the Westinghouse Corporation sponsored research into how cities could shape their built environments to deter what they called “criminals” from certain spaces. The prescription was clinical in its cruelty including harsher lights that assault the senses, benches designed to prevent anyone from sitting too long, desolate conditions that make lingering impossible. The goal was ultimately to make public space inhospitable for people who were deemed “undesirables.”

“So they had this whole study,” Bryan tells me, “That study went to three different cities… and they looked at neighborhoods, they looked at commercial corridors, and they looked at schools and how they might be able to shape space or define space so that, again, quote, unquote, ‘criminals’ would be deterred in some aspects.”

“And what they found was that none of this stuff worked, but they were going to do it anyway.”

I sat, listening.

“And so we know that it wasn’t a theory of practice. It’s the practice, right? It is the practice of creating spaces that actively deter people from engaging in those spaces.”

And fifty years later, despite the research showing it doesn’t work, cities across the country, including Kansas City, are still using it. Often times proudly declaring so. This is what can be called an architecture of violence. And this is what Bryan, the newly appointed president of NOMA, has dedicated his life to dismantling.

Triage and Transformation

Lee took the helm of NOMA on Jan. 1, 2025. “Four days later, someone tried to blow up New Orleans. Five days after that, the West Coast went up in flames. Two weeks into his presidency, Trump began tearing up all the inner workings of any version of a system that was able to protect us,” Lee tells me.

“Not that it was ever really fully protecting us,” he clarifies, “but all of the last threads of sanity were detached.”

The executive orders came fast: attacks on immigrants, slashing of federal funding, national guard occupations, threats to federal funding for institutions that supported equity work, the gutting of procurement processes that had created pathways for small, minority-owned firms to compete for projects.

“A lot of the work that we did this year was centered around triage, which is not what I expected, not what I wanted to be doing, necessarily,” Lee admits. Despite this, NOMA chapters across the country began activating their networks. The development of the Altadena rebuild coalition, a coalition dedicated to providing fire-rebuild expertise and connecting residents with minority design and construction professionals was rapidly deployed after the California fires. This successful model Lee told me he wants to replicate across the country. NOMA also put 2,500 students through Project Pipeline, their youth education program for cultivating young Black architects.

“That’s one thing about Blackness that I am pretty adamant that we kind of maintain as in the forefront of our conversations,” he says. “The creativity, the necessity to do more with little, and to create new worlds, like we’ve always had to create new worlds with almost nothing attached to that.”

The Hardware of Oppression

At 41, Lee carries himself with the bearing of someone who has spent two decades in the trenches of design justice. As the founder of Colloqate Design, a New Orleans-based practice that operates at the intersection of architecture, organizing, and community power-building, he’s built a career on the singular premise that “for every injustice in the world, there is an architecture, a plan and a design that has been built to sustain it.”

This framework rejects the sanitized, apolitical pose that architecture often strikes (and which I myself was most familiar with). It diverts from the lie that buildings are neutral, that design is just aesthetics or that space has no relationship to power.

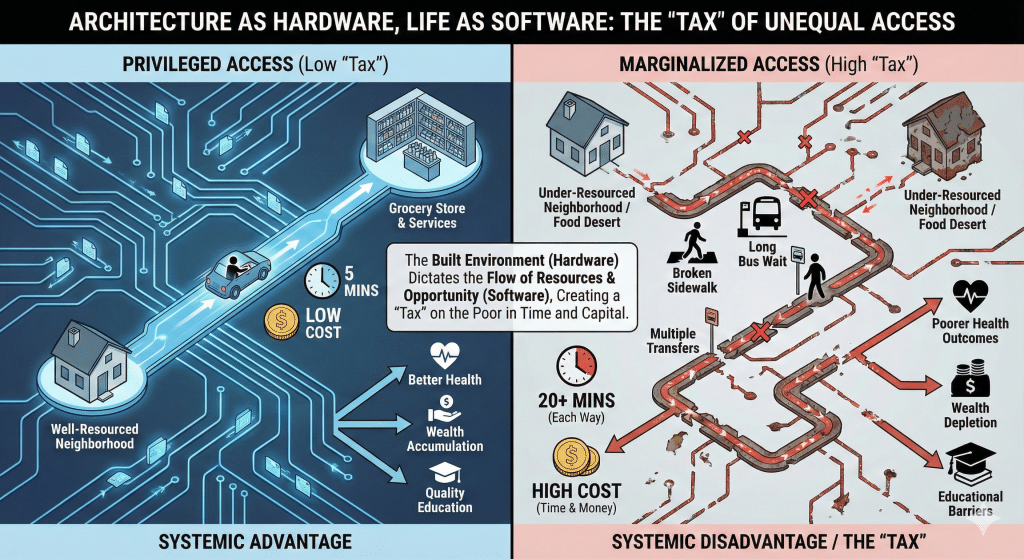

“Architecture is the hardware to the software of life” he explains to me, his hands animated as he talks. “And so if you have to travel 20 minutes to get to groceries, what does that tell you? That is a tax on the poor. That is a tax on those who don’t have vehicles in both time and capital. So the emphasis of this is really just that, when you look at all of the leading determinant factors of health, wealth, education, they all have a direct tie to the spaces we create around them.”

The example is particularly fitting in Kansas City. Just six weeks before the NOMA conference, one of the city’s largest Black-owned grocery stores closed its doors, plunging thousands of Black residents into extreme food insecurity. On that exact same intersection at 31st & Prospect, the city had recently moved the bus stop, citing too many “problematic people” (which can also be interpreted as poor, unhoused and Black) congregating in the area. Rather than address the underlying conditions that had people gathering there in the first place (poverty, lack of access to community resources, unstable housing, addiction resources), the city turned to carceral strategies like building a $500 million jail, removing bus benches and moving the bus stop entirely.

Such strategies are textbook examples of “Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED).”

As Lee explained in our conversation, a 1993 evaluation of those original Westinghouse studies found they produced “inconsistent and temporary effects.” Decades of research since has been “inconclusive and much criticised,” with studies showing it’s “ineffective against violent crimes” and often just displaces problems rather than solving them. In Kansas City, that has absolutely been the case as many residents decry that the violence has not reduced at all, and instead only become more disparate up and down Prospect.

The point here is not to deny that violence, drug abuse, and lack of safety exist in the area. Rather, it’s to acknowledge that simply altering a space does nothing to address the fact that people are starving and resort to stealing bread and baby formula for survival, or that housing insecurity can drive someone to begin abusing drugs. CPTED ignores these realities, opting instead for a quick aesthetic “fix.”

It is a strategy of violence, carceral ideology given physical form, punishment poured into the built environment. And it remains a core part of KCPD’s multi-pronged criminalization strategy.

In fact it’s explicitly named in KCPD’s 2024 Crime Plan. Page 6 explicitly directs its cops to conduct “Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) surveys” across the city. The same discredited pseudoscience, now official policy.

“Yeah, just kind of crazy to see, right here, it’s happening,” Bryan tells me after I describe the bus stop situation at 31st & Prospect, “but of course, it’s a system and a way of thinking that it’s happening in many other places, too.”

From Sicily to Trenton: The Making of an Abolitionist Architect

To understand Lee’s political clarity about space and power, you have to understand the journey that shaped him. He’s a military brat, his mother served in the Air Force, and that childhood of movement gave him a comparative framework.

“I grew up… I got a chance to see a lot of different conditions across the world, but the two conditions that were most significant to me was Trenton, New Jersey and Comiso, Sicily,” he tells me.

In Comiso, he saw a city built for human connection. “The shopping, the housing, the parks, the plazas. It was all crafted so that people could care for one another. It was crafted so that elders and young people had the same space to interact in.”

Then he came back to Trenton at age 10. “I saw a place that was a machine. I saw a cityscape… I saw a space that did not care for how people interacted with one another, how people engaged with one another in their city or in their towns.”

Even at 10, before he had the language for it, Lee recognized the patterns. American cities had been designed for cars, for commerce, for isolation. Not for life or community.

“At that point, I was like, I want to draw a house for my grandmother, and I want to build this house for my grandmother, and my parents said, that is what an architect does. So from that point on, I kind of just ran with it.”

His grandmother’s house in Trenton was the center of everything, where all the family gathered, where connection happened. “But the space didn’t necessarily hold that,” Lee says. The physical structure couldn’t contain the energy and love that filled it. That gap between what was and what could be became the animating question of his life’s work.

But there’s another layer to Lee’s family history that he only recently discovered. His family has owned about 180 acres of land in North Carolina since 1912. They built homes on it. And in 1921, they built one of the 5,500 Rosenwald schools, community-funded schools for Black children during segregation, developed through a partnership between Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington.

“Just having the kind of connectedness of Booker T and obviously there’s a lot of conversation between W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T Washington, and we can continue to go down that route forever. But that is the stuff that influenced me,” Lee says.

This genealogy matters. Lee comes from Black builders, from people who created the infrastructure of Black education and Black community when the state aimed for nothing short of cultural and symbolic genocide. That tradition of building freedom — literally constructing it — runs through his work.

“I Didn’t Know There Was a Black Architect Until I Was 16”

Despite growing up wanting to be an architect, despite drawing constantly, and despite that clear sense of purpose, Lee didn’t see a Black architect until he was 16 years old.

He spent sixteen years imagining himself in a profession where he’d never seen someone who looked like him succeed.

“So I was reading a lot of other stuff, I was reading, you know, Malcolm X, Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King, bell hooks… I was reading a lot of other stuff that kind of influenced how I thought about the world more properly.”

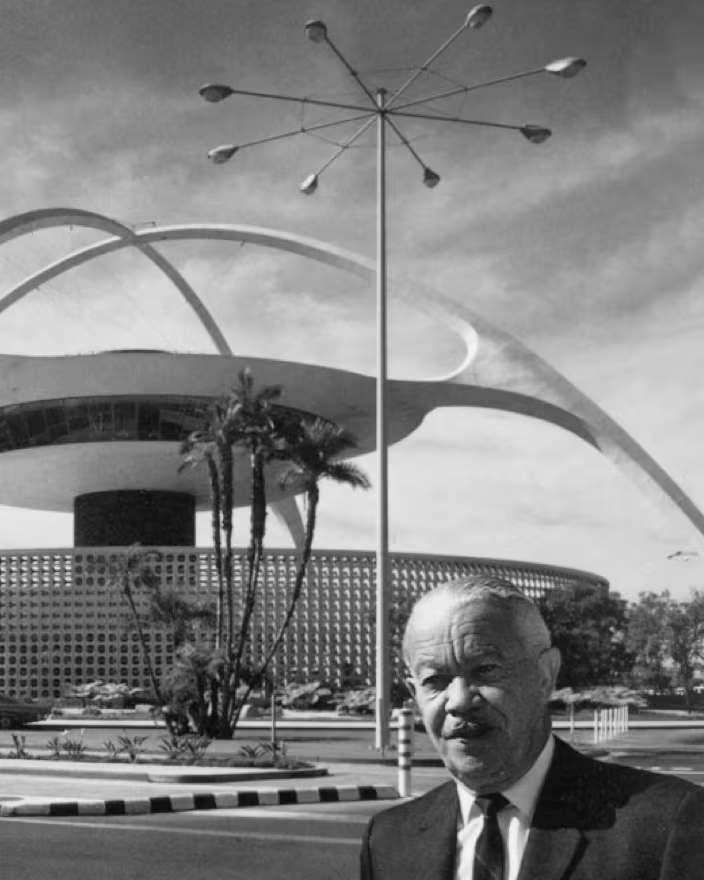

The first Black architect he ever encountered was Curtis Moody. And then he learned about Paul Revere Williams, who designed over 3,000 homes and buildings across Los Angeles, all while existing within a viciously racist system. Williams had to learn to draw and write upside down because he couldn’t sit on the same side of the table as his white clients.

“Those types of things were always the ‘the fuck is going on?'” Lee recalls.

Lee’s path to NOMA began as a student at Ohio State University, after transferring from Florida A&M, a historically Black university, where he’d been playing football.

“I went from a majority Black student body to a majority white student body, with exponentially more students. I found myself a bit lost, struggling to understand what I wanted to do. During my first year at Ohio State, I didn’t understand the value of architecture anymore. I didn’t understand why or who we were doing things for.”

That’s when he helped co-found the first Ohio State NOMA chapter in 2004.

“It was a huge moment for me, and it changed my life.”

Twenty years later, he’s leading the organization.

“Good Leaders Are Good Followers”

Toward the end of our conversation, I asked Lee for any advice he’d offer to young Black architects and designers coming up in this moment.

“Good leaders are good followers,” he said. “I know it sounds super simple and maybe cliché…When I say good leaders are good followers, it means really being able to listen, find empathy, share your voice, and be able to understand and honor someone else’s voice, their story, their truth. Even if their truth is different than yours, it still is their truth.”

This is the opposite of the Great Man theory of leadership that architecture loves to celebrate, the lone genius, the singular vision, the architect as auteur. Lee is talking about collective work, about building with and for communities, about recognizing that the people most impacted by injustice should be leading the fight against it.

“Be patient with yourself. Find community, whatever that community looks like,” he continues. “As you start to grow into your own purpose, be curious as hell.”

He describes a practice he developed in his twenties: “There was one day where I just said I am going to write down every question I have about this world, and I’m going to just seek out those things.”

That curiosity is what makes liberatory architecture possible. Because you have to be able to imagine something radically different from what exists.

“If you actually want to fight and change the world we live in, we actually have to understand it, not just in its structure, but in its quirks, not just in its direction or directive, but in its obscurities.”

And then, critically: “Say no to say yes. Don’t overburden yourself in this world. You have to take care of yourself. You have to be able to breathe, eat, find joy.”

Beyond Destruction: The Architecture of What Comes Next

Bryan C. Lee Jr. is leading NOMA at a moment when the connections between architecture and oppression have never been more visible.

But he’s also leading at a moment when the possibilities for liberatory design have never been more urgent. Because if architecture has been weaponized against Black people, it can also be reclaimed as a tool for abolition and for freedom.

And ultimately, this is the work. Understanding how oppression is built. And then building something else.

“Architecture has the power to speak the language of the people it serves and we have to be willing to serve those without power,” Lee says. “We can choose to be a profession and organization that slips into the cozy niche assertion that architecture is too large to deal with the small nuanced considerations in our communities yet too small to address the larger systemic issues in our society. Or, through advocacy, policy, design and partnerships, we can choose to motivate and build bridges to the future we want to see.”

The work of abolition—and yes, that’s what this is—is often framed as destruction. Tearing down prisons, defunding police, dismantling systems. But it’s also deeply generative. It’s about building the world we need. Building the spaces where we can be free. Building the infrastructure of liberation.

This is what Lee learned from his grandmother’s house, from those Rosenwald schools his family built, from every Black builder who created community when the state offered only violence. We’ve always known how to build freedom. We’ve always had to.

As we finish breakfast and Lee prepares for his trip home, I think about that house he wanted to build for his grandmother at age 10. About the space that couldn’t quite hold all the love and community that filled it. About his life’s work trying to create structures worthy of Black life, Black joy, and Black futures.

Bryan C. Lee Jr., NOMA, and a new era of radical Black designers are creating that blueprint. And they’re making sure we all have the tools to build it together.