Behind the brickwork and neon signs of Kansas City’s Westport entertainment district, a federal lawsuit alleges an invisible regime decides who belongs and who does not.

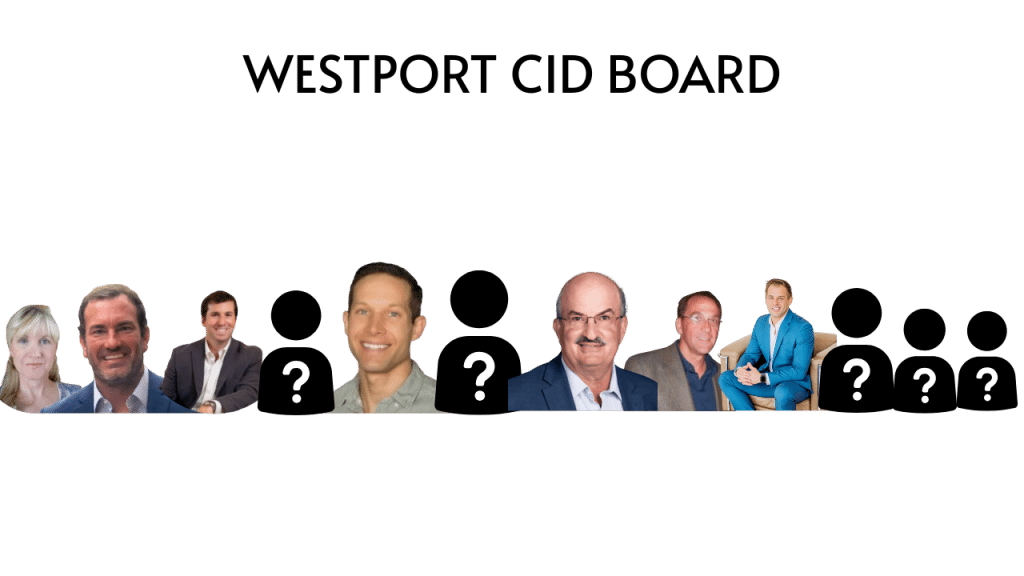

The mechanism of control, according to court documents, is a secret “Good Neighbor Agreement.” The price of entry is compliance. And the enforcers are an all-white, twelve-member board of the Westport Community Improvement District (CID).

“We won’t sign a consent of any kind, even beer and wine, unless we have a good neighbor agreement in place,” CID members told prospective business owners, according to a lawsuit that claims to quote an audio recording.

And for those who resist?

“We do everything we can to put them out of business.”

Those recorded statements are at the heart of a federal civil rights and RICO case that accuses Westport’s power brokers of a coordinated conspiracy to keep Black-owned businesses out. The defendants have denied all wrongdoing, and the claims have not yet been proven in court. But a federal judge has ruled there is enough evidence to proceed toward a trial.

At the center of this lawsuit is plaintiff Christopher Lee, a Black restaurateur whose lease, livelihood, and vision for a Westport venue were allegedly sabotaged by a coordinated effort to keep Black-owned businesses out of the district.

On October 7, 2025, U.S. District Judge Roseann Ketchmark allowed more defendants to be added to the case. She found that the plaintiffs had adequately alleged a coordinated effort driven by a “common discriminatory purpose,” to lock Black-owned businesses out of one of Kansas City’s most profitable commercial corridors.

A NOTE ON JOURNALISM AND SOURCING: Every assertion of fact in this story is derived from federal court filings, including the Second Amended Complaint, Judge Ketchmark’s order, and evidence submitted to the court. The defendants have denied all allegations, and none of the claims have been proven. This story reflects the current state of the litigation.

The receipts described in the complaint are damning. Text messages between Westport community property owners conspiring to strategically “eliminate ‘problematic’ owners in Westport, and for the purpose of preventing ‘problematic’ people from patronizing Westport.”

A secret “No Play List“ banning popular Black artists like Beyoncé, Meg the Stallion, Drake, Cardi B, Kendrick Lamar, Migos, and Travis Scott from being played at venues. Landlords admitting on tape that they had no legal grounds to block a Black restaurateur’s lease, but doing it anyway after the CID intervened. And a twelve-member CID board, every single member white, acting as gatekeepers over who gets liquor licenses and who gets “turned in to Regulated Industries,” the city agency that polices alcohol permits.”

If Lee’s claims are proven, this is what a modern conspiracy to permeate segregation throughout a community looks like. Not burning crosses. Not explicit laws. But contracts weaponized as cudgels, liquor licenses held hostage, and music turned into evidence of who deserves to belong.

Welcome to what can only be described as a new form of Jim Crow in Kansas City.

THE COUP: How a Black Restaurateur Lost His Lease in One Week

According to court documents, Christopher Lee did everything right. He negotiated for weeks. Flew to California to meet the property owner. Signed a 10-year lease for 4128 Broadway, the former Ale House location in the heart of Westport, on October 21, 2024. Paid a $10,000 deposit two days later.

Then his concept, a restaurant and lounge called Euphoric Bar & Lounge, quickly started generating buzz on social media, especially among Black community organizers and promoters. To handle hiring and administrative logistics, Lee used his hospitality and staffing company, Ale House West, to host a recruitment event for Euphoric Bar & Lounge on October 23, 2024.

He said the name “Ale House West”— a legacy brand he used solely for business administration — sparked confusion online, as some assumed the defunct “Ale House” bar was reopening. According to filings, Westport CID members seized on that misunderstanding, disregarding Lee’s clarification that Ale House West was merely a hiring service, not the name of the new venue.

People talked about jobs. A reopening. The energy you get when a neighborhood is about to see something new.

That’s when everything stopped.

The keys never came. The landlord, Harold Brody, whose business, 4128 Broadway, LLC, held the lease, allegedly told Lee to change the name, to “target an older crowd,” and to avoid “that young hip-hop crowd.” By the following week, the locks stayed shut. When Lee pointed out Brody was breaching the lease, the owner allegedly responded: “sue me.”

What happened between the deposit and the dead bolt? According to the lawsuit: the Westport power structure intervened.

Court documents describe a web of phone calls, pressure, and what plaintiffs frame as a shakedown. Brody admitted on a recorded call that Lee wasn’t actually in breach of the lease, stating, “I’m not suggesting that there’s a breach at all it’s just.. it didn’t pan out.” He insisted Lee had to “convince” the Wesport CID.

Within months, the same space was re-leased to a different operator. A white operator. Lee’s deposit? Accepted. His business plan? Denied. His lease? Treated like it never existed.

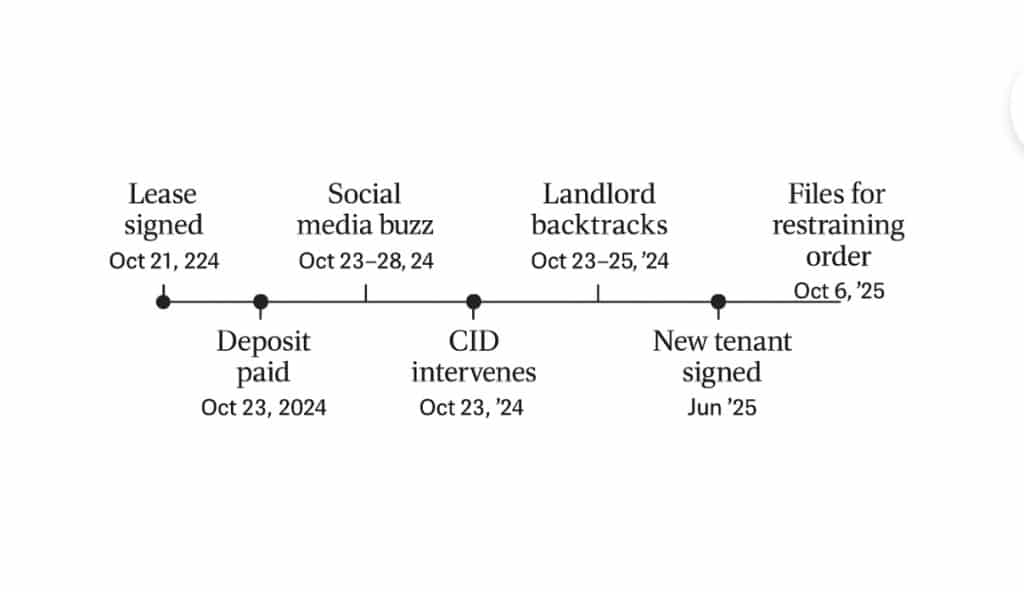

The timeline, submitted to the federal court, is as follows:

THE DEFENDANTS’ RESPONSE: Denial and the Legal Road Ahead

The defendants have denied wrongdoing in their legal filings and through their social media platforms. A spokesperson from the Westport CID released the following statement to several news outlets:

“The Westport Community Improvement District (CID) and its board members strongly refute the allegations made by Euphoric, UniKC and The Sourze. While we cannot comment on the specifics of ongoing legal matters, we are confident that the facts will demonstrate the baselessness of these allegations against the CID and its board members.

For decades… We believe that diversity among business owners and patrons isn’t just the right thing to do—it’s good business…”

Discovery will pull emails, board minutes, financial records, and testimony under oath. If the defendants have evidence that clears them — proof that the “Good Neighbor Agreement” is legitimate, that liquor consent procedures were fair, that business decisions were based on merit rather than race — they’ll present it.

But here’s the thing: the plaintiffs don’t have to prove intent in every defendant’s heart. Under civil rights and RICO law, they have to show a pattern. That a network of actors, through coordinated conduct, achieved a discriminatory result. And Judge Ketchmark has already ruled there’s enough smoke to look for the fire.

The defendants’ best defense would be: “We followed standard business practices. We applied the same rules to everyone. The plaintiffs failed for legitimate reasons unrelated to race.”

The plaintiffs’ response will be: “Then explain the tapes. Explain the texts. Explain the music ban. Explain why an all-white board gets to decide which Black-owned concepts are ‘problematic’ before they even open.”

That’s the fight. And it’s happening in a federal courtroom, under penalty of perjury, with RICO damages on the table.

THE SYSTEM: A Secret Agreement and the Power to Destroy

The system alleged in the Westport lawsuit functions as a modern-day commercial covenant, updating J.C. Nichols’ playbook of exclusion for the 21st century. Where Nichols used racially restrictive deeds to keep Black residents out, the lawsuit claims the all-white CID wields a secret ‘Good Neighbor Agreement’ and control over liquor licenses to keep Black businesses out.

Since 2013, according to the complaint, new businesses seeking alcohol permits have been coerced into signing the one-sided “Good Neighbor Agreement.” The secretive document is kept in the CID office, not given to tenants in advance, not posted publicly, and not subject to negotiation.

If you don’t sign? Nearby property owners, many of whom sit on the CID board or are aligned with it, refuse to sign the city consents required for your liquor license. No signatures, no booze. No booze, no business. No business, no livelihood.

The newly amended complaint refers to quotes by agents, board members, and others affiliated with the CID to paint the picture:

“We won’t sign a consent… of any kind, even beer and wine, unless we have a good neighbor agreement in place.”

“We go after them with a vengeance because when we don’t have a contractual agreement, we do everything we can to put them out of business.”

The lawsuit frames it as extortion dressed as neighborhood stewardship.

To make matters worse, many Kansas City business owners see the city’s liquor licensing process as a labyrinth by design. State law and local ordinance create a series of checkpoints: applications, hearings, neighbor consent forms. Westport’s CID in particular, the lawsuit argues, turned that complexity into a chokepoint, where the all-white, self-interested board decides not just who opens a bar, but what kind of bar, and for whom.

The “Good Neighbor Agreement” itself remains murky. When the plaintiffs sought to see the full terms, they were stonewalled. When they tried to open without signing, they were blackballed with threats to terminate their liquor licenses.

According to multiple accounts, businesses that resisted compliance with the Westport CID faced coordinated retaliation, often in the form of liquor license intimidation or sudden enforcement actions. The CID and its affiliates also sought to influence nightlife culture more directly, pressuring venues not to hire certain Black DJs.

In one instance, a business owner admitted to signing the agreement under duress after being told he could not employ Kansas City DJ Steven Davis — whose own lawsuit also includes a RICO charge and corroborates many of these same allegations. One message allegedly sent among CID-aligned figures discussed “strategic moves” to eliminate people deemed “problematic” from Westport. Another outlined plans to pressure landlords into breaking leases when Black-led concepts surfaced.

BANNED: A Target On Black Culture & Secret “No Play List”

Then there’s the infamous playlist. While this aspect is widely known and no longer breaking news, it remains a damning component of an ever-mounting pile of racist attitudes and actions.

A prominent Westport operator, Brett Allred, maintained a “No Play List”—a literal blacklist of songs and artists banned from being played in his venues. Including former bars like Bridgers and Johnny Kaws.

The list reads like a Billboard Hot 100 for Black music: Meg Thee Stallion, Cardi B, Kendrick Lamar, Migos, Travis Scott. To be clear, these are not just “drill” songs or “trap” music most commonly demonized as “violence-inciting”. This list even included Beyoncé.

The lawsuit describes efforts to “whitewash” Westport and punish any venue that booked a Black DJ who might “attract” a Black crowd. Any DJ who brought Black patrons was allegedly told they weren’t welcome back. Promoter whose events drew Black audiences were allegedly targeted by the CID, and their venue connections shut down through administrative and liquor license pressure.

That pattern is echoed in a newly filed case. Steven Davis, a Black DJ known professionally as “DJ Street King,” filed a separate civil rights lawsuit in 2024 against CID board member Brett Allred, the Westport CID, The Roadhouse Group, Inc. (doing business as Firefly Lounge at 4116 Pennsylvania Ave.), and Firefly’s owner, Todd Gambal. Davis alleges that his services were terminated because of racial discrimination involving the CID, Allred, Gambal, and Roadhouse. His complaint claims that Allred threatened Firefly’s liquor license if the venue continued to hire DJ Street King, leading to his removal from the lineup, according to court filings.

THE MECHANISM: How Community Improvement Districts Became Private Governments

Community Improvement Districts are legal entities made up of neighborhood property owners who vote to tax themselves and control how the money is used within their district.

CIDs are sold to the public as organizations that serve the “public good”: cleaner streets, better lighting, business promotion and the like.

Kansas City annexed Westport, once its own town, in 1897, fully incorporating it into the city’s jurisdiction. The area evolved in the 20th century into a nightlife and entertainment hub, and the Westport CID was established in 2003, according to city clerk records, with the supposed aim to manage and fund improvements in the district’s core commercial blocks. On paper, CIDs appear to be appropriate and democratic institutions, even helpful or beneficial. In practice however, they’re often racially-motivated and controlled by whoever owns the most property and has the most legal power to weaponize. In Westport’s case, that’s a twelve-member board, all white, many with financial interests in bars, restaurants, and real estate in the district.

Photos sourced from publicly available LinkedIn profiles. Blank silhouettes represent CID board members whose identities could not be independently verified at the time of publication. All individuals are current or recent members of the Westport CID board, a public body named in the federal civil rights and RICO lawsuit. All deny wrongdoing, and the allegations remain unproven at this stage.

And in Kansas City, CIDs have real power. They can levy special taxes. They lobby city officials (they were at the forefront of the recent movement for massive jail expansions in Kansas City). They coordinate with Regulated Industries, and they represent the district in zoning and planning discussions.

But unlike elected city councils, CID boards aren’t accountable to voters. They’re accountable to property owners, and in Westport, property ownership is overwhelmingly white and concentrated in a small network of families and businesses who’ve been in the area for decades.

The lawsuit describes the CID as functioning less like a business improvement district and more like a private government, one that uses its leverage over liquor licenses and lease negotiations to enforce unwritten rules about who belongs and who doesn’t.

And when you look at the receipts, the recorded threats, the secret agreements, the music bans, it’s hard to see how the CID’s actions serve any “public” interest. Unless, of course, you define “the public” the way infamous Kansas City developer J.C. Nichols did: white, wealthy, and willing to pay top dollar to keep it that way.

THE RICO ANGLE: Not Just Another Civil Rights Case

On October 7, 2025, Judge Roseann Ketchmark issued an order that should make every Westport landlord, every CID board member, and every bar owner named in this lawsuit very nervous.

She granted the plaintiffs’ motion to add more defendants and allowed the case to proceed under both federal civil rights statutes and the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO. The lawsuit claims the Westport CID and its network operated like a racketeering enterprise, using threats and coercion to control the district’s economy.

RICO was established in 1970 to take down the mob. It allows prosecutors and plaintiffs to target not just individual crimes, but an entire enterprise that operates through a pattern of illegal conduct: extortion, fraud, threats.

Why does RICO apply here? Because the plaintiffs aren’t just alleging isolated acts of discrimination. They’re alleging an organized system, a network of Kansas City Agents, landlords, bar owners, and CID board members, used coercion, threats, and fraud to control who could open businesses in Westport and who got driven out.

Their case hinges on three elements:

- An enterprise: The CID and its aligned property owners and businesses.

- A pattern of racketeering activity: Threats to liquor licenses, deceptive lease terms, racial exclusion.

- Economic harm: Lee lost $10,000 and his business. Others never got to open. Some are forced to hand over 20% of drink revenue if they won’t sign the “Good Neighbor Agreement.”

If proven, the defendants could face treble damages under RICO. That means triple the economic harm, plus attorneys’ fees.

Judge Ketchmark compared this case to Mosley v. General Motors Corp., a 1974 federal decision that allowed multiple acts of discrimination to be tried together if they advanced a common, discriminatory purpose.

Here, the purpose, as alleged: Shutting out African-American business owners across Westport.

Translation: the judge believes the plaintiffs have made a strong enough case racial discrimination against each of the defendants, all Westport power players, to allow adding them to the case and moving forward in finding out a modern Jim Crow conspiracy really did hide behind talk of “neighborhood standards” and “good neighbor” policies.

Now discovery is underway. Emails, texts, board minutes, liquor consents, and recordings are being subpoenaed. The defendants will have to answer for what they said, what they signed, and what they enforced.

The clock is ticking. The receipts are mounting. And the conspiracy, if there is one, may soon be dragged into the light.

THE RECEIPTS: What’s Actually on Record

Let’s be clear about what’s documented and what’s alleged. The following are direct quotes and facts cited in the court filings, derived from recordings, text messages, and pleadings:

On tape:

- Westport agents stating they “won’t sign a consent… of any kind even beer and wine unless we have a good neighbor agreement in place.”

- Agents bragging that if an owner “step[s] out of bounds,” they’ll “turn you in to Regulated Industries” and “go after you with a vengeance.”

In text messages:

- Discussions among Westport figures about “strategic moves” to keep out “problematic” owners and patrons.

- Plans to pressure landlords into killing leases when Black-led concepts generate buzz.

In the Lease Timeline:

- Christopher Lee signed a 10-year lease on October 21, 2024.

- He paid a $10,000 deposit on October 23, 2024.

- Keys were never delivered.

- The landlord admitted on a recorded call that there was “not necessarily a breach” but refused to honor the lease after CID intervention.

- By mid-2025, the same space was leased to a white tenant.

In the “No Play List”:

- A documented list of banned artists, including Beyoncé, Jay-Z, Drake, Cardi B, Kendrick Lamar, Migos, and Travis Scott.

- Allegations that venues booking Black DJs or hosting events that attracted Black audiences faced retaliation through liquor license threats.

From the Court:

- Judge Ketchmark’s October 7, 2025 order allowing the case to expand based on sufficient assertions of “a common discriminatory purpose.”

The judge’s finding that the case raises the question of whether a conspiracy existed, a question that can go before a jury.

THE BIGGER QUESTION: Who Decides What Westport Is For?

At the bottom line, this case is about power and belonging.

Who gets to decide what Westport is? Is it a public commercial district, part of Kansas City’s shared fabric, where anyone with a solid business plan and capital should be able to compete? Or is it a private club, where an all-white board enforces unwritten rules about music, clientele, and “neighborhood character”?

And who gets to be at the center of Kansas City’s cultural economy? The people who already own property and sit on boards? Or the entrepreneur, many of them Black, many of them young, many of them bringing new energy, who see opportunity and want to build?

Kansas City knows this story. The name changes, evolved gentrification methods, with the same outcomes: Black people get pushed out, while white property owners profit.

Long before Westport became a nightlife district, it was home to Steptoe, one of Kansas City’s first Black settlements. Before freedpeople founded Steptoe in the late 1800s and built homes, churches, and schools west of Broadway, enslaved people were sold in the Westport area, including out of the basement of what is now Kelly’s Westport Inn.

Over time, the neighborhood was systematically dismantled, its residents displaced through redevelopment and its history buried beneath St. Luke’s Hospital’s expansion. As early as 2004, historians warned that a $150 million redevelopment plan would wipe Steptoe off the map. Today, that erasure continues under the guise of “progress.”

The Troost divide still holds. J.C. Nichols’ racist covenants are technically illegal but still shape who lives where and who can afford what.

And now, in 2025, a Black restaurateur signs a lease, pays a deposit, and gets locked out because the wrong people got excited on social media.

EDITOR’S NOTE

The Kansas City Defender will continue to follow this case as it moves through federal court. We will publish updates as key rulings, evidence, and testimony emerge.

The defendants in this case have the right to defend themselves, to present evidence, and to challenge every claim. That process is underway. What’s not up for debate is that this case exists, that it’s been allowed to expand, and that a federal judge believes there’s enough here to ask: Did Westport run a conspiracy?

We’ll keep asking until there’s an answer.

— The Kansas City Defender Editorial Team

Got tips, documents, or testimony related to this case or to discrimination in Kansas City’s hospitality and entertainment industries? Contact us securely at tips@kcdefender.com